The Foundation: Flawless Automotive 3D Topology

In the expansive and continually evolving world of 3D visualization, automotive models stand as a pinnacle of complexity, precision, and aesthetic appeal. From stunning photorealistic renders that grace advertising campaigns to high-performance game assets driving immersive virtual experiences, the demand for exceptionally crafted 3D car models has never been higher. Mastering the art and science behind these assets requires a deep understanding of intricate workflows, technical specifications, and industry best practices.

Whether you’re an automotive designer visualizing a new concept, a game developer building the next racing sensation, an architect integrating vehicles into a scene, or a student aspiring to enter the competitive field of 3D, the journey from a raw mesh to a polished, optimized 3D car model is fraught with technical nuances. This comprehensive guide will take you through the critical stages of developing, optimizing, and deploying high-quality 3D car models across various applications, including rendering, game development, AR/VR, and even 3D printing. We’ll delve into the foundational principles of topology, sophisticated UV mapping, advanced PBR material creation, rendering techniques, and crucial optimization strategies, equipping you with the knowledge to elevate your 3D automotive projects.

The Foundation: Flawless Automotive 3D Topology

The bedrock of any high-quality 3D car model is its topology. This refers to the arrangement of vertices, edges, and faces that define the mesh. For automotive subjects, clean and efficient topology is paramount, impacting everything from the smoothness of reflections on curved surfaces to the ease of UV mapping and deformation. A meticulously modeled car will feature a predominantly quad-based mesh, ensuring predictable subdivision behavior and seamless integration with various pipelines. The goal is to create a structure that accurately represents the vehicle’s form while being as efficient as possible, balancing detail with performance.

Achieving this requires a methodical approach to edge flow, ensuring that edge loops follow the natural contours and design lines of the car. This not only makes the model visually appealing but also facilitates adding detail, creating panel gaps, and animating parts if necessary. Poor topology, characterized by unevenly distributed polygons, excessive triangles in flat areas, or erratic edge flow, can lead to undesirable pinching, shading artifacts, and difficulties in subsequent production stages. Industry professionals often spend a significant portion of their modeling time meticulously refining topology to ensure a robust and flexible asset.

Principles of Clean Quad Topology

The golden rule for automotive topology is to prioritize quads (four-sided polygons). While triangles are permissible in very specific, flat, and non-deforming areas, an excessive number can lead to unpredictable shading and subdivision issues. Crucial to clean topology are edge loops: continuous chains of edges that run along the model’s surface. For cars, these loops should meticulously follow the design lines of the body panels, wheel arches, windows, and creases. Proper edge flow allows for controlled deformation and smooth transitions between different surface characteristics.

Another key concept is managing poles – vertices where more or less than four edges meet. While unavoidable in some areas, minimizing N-gons (polygons with more than four sides) and ensuring poles are placed in areas of low curvature or detail is essential to prevent shading artifacts. For instance, aiming for 5-edge poles in convex areas and 3-edge poles in concave areas can help maintain smooth surfaces. When working with subdivision surfaces (like OpenSubdiv in 3ds Max or Blender’s Subdivision Surface modifier), clean quad topology ensures that the smoothed mesh remains true to the original design, free from unexpected bumps or dips, even at high subdivision levels. A typical high-detail render-ready car model might range from 150,000 to 500,000 polygons for the base mesh, which can then be subdivided to millions for extreme close-ups, while a game-ready asset targets much lower counts, often between 50,000 and 150,000 for the highest LOD.

Specialized Techniques for Automotive Surfaces

Automotive design is characterized by sleek, often subtly curved surfaces that transition into sharp, well-defined creases. Replicating these nuances requires specific modeling techniques. For sharp edges and panel gaps, supporting edge loops are essential. These are additional edge loops placed very close to the hard edge, preventing excessive rounding when subdivision modifiers are applied. The proximity of these supporting loops dictates the sharpness of the edge. For instance, to create a crisp panel gap, you might duplicate a series of edges, slightly offset them, and then bridge them to create the gap, ensuring both sides maintain their curvature.

Maintaining curvature across large, seemingly flat panels is another challenge. It’s rarely a truly flat surface; often, there are subtle convex or concave forms designed to catch light in specific ways. Using tools like “flow connect” or “connect edges” judiciously helps distribute polygons evenly, preventing “stretching” or “pinching” that can occur if polygon density varies too much. When modeling complex components like headlights or intricate wheel designs, breaking them down into simpler, manageable parts before combining them can streamline the process. Always aim for symmetry where appropriate to reduce modeling time and ensure consistency across the vehicle. This meticulous attention to detail at the topology stage pays dividends throughout the entire production pipeline.

The Art of Surface Detail: UV Mapping and Texturing for Cars

Once the topology is solid, the next crucial step is UV mapping and texturing. UV mapping is the process of unfolding the 3D mesh into a 2D space, allowing 2D textures to be applied accurately to the model’s surface. For the intricate geometry of a car, strategic UV mapping is vital for achieving realistic surface details, preventing texture stretching, and optimizing material application. Poor UVs can lead to distorted textures, visible seams, and inefficient texture memory usage, especially critical for real-time applications.

Texturing then brings life to these UV layouts, allowing you to define everything from the subtle metallic flakes in the car paint to the intricate patterns on interior fabrics and the worn appearance of tires. Modern workflows heavily rely on Physically Based Rendering (PBR) texturing, which demands a precise understanding of how various maps (Albedo, Roughness, Metalness, Normal) interact to simulate real-world material properties. The combination of well-executed UVs and high-quality PBR textures transforms a geometric mesh into a visually compelling and believable automotive asset.

Strategic UV Unwrapping for Complex Geometry

UV unwrapping a car is a delicate balance between minimizing seams, reducing distortion, and optimizing texture space. The general strategy involves segmenting the car into logical, manageable parts (e.g., hood, doors, roof, bumpers, wheels, interior elements) and unwrapping each section individually. For large, curved panels like the hood or roof, a planar or cylindrical projection might be a good starting point, followed by manual seam placement to hide them in less visible areas, such as under panel gaps or along hard edges. Tools like “Pelt mapping” in 3ds Max or the “Follow Active Quads” option in Blender are invaluable for achieving even UV distribution and minimizing stretch.

Maintaining consistent Texel Density across the entire model is also critical. Texel density refers to the number of pixels per unit of 3D space. Ensuring similar texel density for all visible parts prevents some areas from appearing blurry while others are crisp. For instance, if a car model uses 4K textures, a section like the hood might occupy a significant portion of the UV space to ensure high detail, while smaller, less visible components might share space or use lower resolution textures if their detail isn’t critical. Many artists use checkerboard patterns during unwrapping to visually inspect for distortion and inconsistent texel density. Non-overlapping UVs are a must for baking accurate normal maps and for consistent PBR material behavior across the model.

Advanced Texturing for Realism

Beyond base colors, the true realism of a car model comes from its intricate texturing. Modern workflows leverage PBR texture sets, typically including Albedo (Base Color), Roughness, Metalness, Normal, and sometimes Height or Ambient Occlusion maps. For car paint, this involves creating a base metallic map, then building layers of clear coat and metallic flakes through shader networks rather than pure texture maps. Scratches, dirt, and wear are often added through secondary texture layers or masks, allowing for non-destructive iteration.

For interior elements, high-resolution textures are crucial for materials like leather, fabric, and plastics. A 4K or even 8K texture resolution for primary body elements is common for high-end rendering, while game assets might use 2K for the main body and 1K or 512px for smaller components, often packed into texture atlases to reduce draw calls. Decals, such as logos, badges, and warning labels, are often handled with separate texture sheets or placed directly on the model via texture projection or secondary UV channels. Utilizing software like Substance Painter or Mari allows artists to paint directly onto the 3D model, ensuring seamless integration and leveraging procedural generators for realistic wear and tear. This holistic approach to texturing ensures that every surface tells a story, contributing to the overall believability of the 3D car model.

Bringing Cars to Life: PBR Materials and Shading Networks

With clean topology and meticulously unwrapped UVs, the next monumental step is defining the materials that give your 3D car model its visual identity. Physically Based Rendering (PBR) has become the industry standard for achieving photorealistic results, moving away from subjective artistic interpretations of light and surface interaction. PBR materials simulate how light behaves in the real world, based on physical properties of surfaces like reflectivity, roughness, and metallicity. This approach ensures that your models look consistent and realistic under various lighting conditions, making them ideal for everything from cinematic renders to real-time game engines. Understanding PBR principles and how to construct sophisticated shader networks is essential for creating compelling automotive visuals.

The complexity of a car’s surface, with its myriad of materials – glossy paint, reflective chrome, matte plastics, intricate carbon fiber, and plush interior fabrics – demands a robust and flexible material system. Shading networks allow artists to layer these properties, combine different textures, and introduce procedural elements to create highly nuanced and detailed materials. Whether you’re working in 3ds Max with Corona or V-Ray, Blender with Cycles, or Maya with Arnold, the underlying principles of PBR remain consistent, ensuring transferability and predictable results across different renderers and applications.

Deconstructing PBR: Albedo, Roughness, Metalness, Normals

At the core of a PBR material are several key maps that define how light interacts with the surface:

- Albedo (Base Color): This map defines the diffuse color of the surface without any lighting information. For metallic surfaces, it represents the color of the reflected light. It should be desaturated for metals and contain no baked-in shadows or highlights.

- Roughness: Controls the microscopic surface irregularities that scatter light. A value of 0 (black) means perfectly smooth and mirror-like (e.g., chrome), while 1 (white) means completely rough and diffuse (e.g., matte plastic). This is crucial for distinguishing between polished paint, dull plastic, and textured rubber.

- Metalness: A binary map (0 or 1) indicating whether a surface is metallic (1) or dielectric (non-metallic, 0). Metallic surfaces reflect light directly, with their reflections taking on the color defined by the Albedo map. Non-metallic surfaces have a fixed Fresnel reflection.

- Normal Map: This map uses RGB values to store directional information, allowing a low-polygon model to display high-detail surface information (like bolts, subtle panel variations, or fabric weaves) without increasing the actual polygon count. It fakes surface detail by altering the way light bounces off the surface.

Additional maps like Ambient Occlusion (for baked-in contact shadows), Height/Displacement (for actual geometric detail), and Opacity can further enhance realism. The correct interplay of these maps ensures physically accurate light interaction, a cornerstone of professional automotive rendering.

Crafting Realistic Car Paint and Interior Shaders

Creating realistic car paint is one of the most challenging aspects of automotive material development due to its layered nature. A typical car paint shader involves:

- Base Metallic Layer: Defined by a metallic Albedo map (often a dark, saturated color) and a low Roughness value.

- Clear Coat Layer: This is a transparent, highly reflective dielectric layer on top of the base. It has its own Roughness value (typically very low for a shiny car) and sometimes a slight color tint. Many renderers offer dedicated ‘Clear Coat’ parameters in their PBR shaders to simplify this.

- Metallic Flakes: For iridescent or metallic paints, a separate layer of procedural or texture-based flakes is often added, scattering light at different angles to create a sparkling effect. This is usually implemented through a micro-normal map or a dedicated flake generator within the shader.

For interior materials, the focus shifts to a wider array of textures and properties. Leather might require detailed normal maps for grain, combined with specific roughness variations to simulate its subtle sheen and wear. Carbon fiber uses a complex blend of intricate normal maps for the weave, coupled with metallic and roughness maps to achieve its characteristic depth and reflection. Fabric shaders rely on detailed normal maps for weave patterns and often utilize subsurface scattering to simulate light penetrating and scattering within the material, giving it a softer, more realistic look. The judicious use of tileable textures, often at 2K or 4K resolution, for repeating patterns (like fabric weaves) and unique textures for specific details (like instrument clusters) ensures both detail and efficiency.

Photorealistic Visions: Advanced Automotive Rendering Workflows

Bringing a 3D car model to life culminates in the rendering process. This is where all the meticulously crafted geometry, UVs, and PBR materials converge under simulated lighting conditions to produce breathtaking images. Achieving photorealism in automotive rendering is an art form that blends technical proficiency with an eye for visual storytelling. It involves choosing the right renderer, understanding its capabilities, setting up complex lighting environments, and extracting various data passes for post-production refinement. The goal is to create images that are indistinguishable from real-world photography, showcasing the vehicle’s design and detail in the most appealing way.

Modern renderers offer incredible power and flexibility, but harnessing them effectively requires knowledge of their specific settings, optimization techniques, and the ability to work with a multi-pass compositing workflow. Whether your output is a still image for advertising, an animation for a product launch, or high-fidelity visualization for automotive configurators, a structured approach to rendering will yield the best results. Platforms like 88cars3d.com offer models already optimized for various rendering engines, providing a solid starting point for these advanced workflows.

Choosing Your Renderer: Corona, V-Ray, Cycles, Arnold

The choice of renderer significantly impacts workflow, render times, and the final aesthetic. Each renderer has its strengths:

- Corona Renderer (3ds Max, Cinema 4D): Renowned for its ease of use and ability to produce stunningly realistic results with minimal tweaking. Its unbiased path tracing engine excels at complex global illumination and subtle light interactions, making it a favorite for architectural and automotive visualization. It’s often praised for its intuitive material system and interactive rendering capabilities.

- V-Ray (3ds Max, Maya, SketchUp, Rhino, Cinema 4D): A long-standing industry standard, V-Ray offers unparalleled flexibility and power. It’s highly optimized for production environments, capable of handling massive scenes and complex effects. While it has a steeper learning curve than Corona, its vast feature set, including robust render elements and production-level tools, makes it a powerhouse for professional studios.

- Cycles (Blender): Blender’s integrated path-tracing renderer, Cycles, has evolved significantly. It’s GPU-accelerated, supports PBR materials natively, and integrates seamlessly with Blender’s ecosystem. Its node-based shader editor is incredibly powerful for crafting complex materials, making it a strong contender for independent artists and small studios.

- Arnold (Maya, 3ds Max, Cinema 4D, Houdini): Developed by Solid Angle and now part of Autodesk, Arnold is a high-performance, unbiased Monte Carlo path tracer. It’s widely used in film and TV production for its robust handling of complex geometry, volumes, and physically accurate lighting. Its strengths lie in its stability and ability to render intricate details with excellent light sampling.

When choosing, consider your existing software ecosystem, project requirements (still image vs. animation), and desired balance between speed and quality. Most professional workflows involve test renders at lower resolutions and quality settings to quickly iterate on lighting and materials before committing to final high-resolution renders.

Render Passes and Compositing for Unparalleled Realism

Achieving truly photorealistic automotive renders often involves a multi-pass rendering and compositing workflow. Instead of rendering a single image, the scene is rendered into multiple ‘passes’ or ‘render elements,’ each containing specific information. Common passes include:

- Beauty Pass: The primary rendered image.

- Diffuse Pass: Only the diffuse color and lighting.

- Reflection Pass: Only specular and reflective components.

- Refraction Pass: For transparent materials like glass.

- Z-Depth Pass: Stores depth information, useful for depth of field and fog effects in compositing.

- Normal Pass: Surface normal information, useful for relighting or post-process effects.

- Object/Material ID Passes (e.g., Cryptomatte): Masks for individual objects or materials, allowing precise selection and adjustment in compositing.

These passes are then brought into a compositing software like Adobe Photoshop, After Effects, Nuke, or DaVinci Resolve. Here, they can be non-destructively combined and adjusted. For instance, you can separately tweak the intensity of reflections on the car paint, adjust the color of the headlights, or add subtle glow effects without re-rendering the entire scene. Compositing also allows for advanced post-processing effects like color grading, vignetting, lens flares, film grain, and subtle atmospheric haze, adding that final layer of polish that transforms a good render into an exceptional one. This modular approach provides immense control and flexibility, making it an indispensable part of high-end automotive visualization pipelines.

Performance Powerhouse: Optimizing 3D Car Models for Game Engines

While photorealistic renders prioritize visual fidelity above all else, integrating 3D car models into real-time environments like game engines introduces a new set of challenges: performance optimization. Game engines like Unity and Unreal Engine need to render thousands, if not millions, of polygons per frame at 30-120 frames per second. An unoptimized, high-polygon car model designed for cinematic rendering would cripple game performance. Therefore, game assets require a distinct approach to modeling, texturing, and material setup to ensure smooth gameplay without sacrificing visual quality.

Optimizing 3D car models for games involves reducing polygon counts, efficiently managing textures, minimizing draw calls, and leveraging techniques like Level of Detail (LODs). The goal is to strike a balance between visual quality and real-time performance, ensuring that players have an immersive experience without lag or stutter. This optimization is crucial for open-world games, racing simulations, and any interactive application where multiple vehicles might be present simultaneously.

LODs and Polycount Management for Real-time Performance

The primary strategy for managing polycount in games is using Level of Detail (LODs). Instead of having a single high-polygon model, multiple versions of the car are created, each with a progressively lower polygon count.

- LOD0 (High-Poly): Used when the car is very close to the camera (e.g., player’s car, in-game cinematics). Typically 50,000 to 150,000 polygons for a hero vehicle, retaining most of the detail.

- LOD1 (Medium-Poly): Used for cars at a moderate distance. Roughly 20,000 to 50,000 polygons, with some smaller details removed or baked into normal maps.

- LOD2 (Low-Poly): For cars further away. Around 5,000 to 20,000 polygons, significant simplification, relying heavily on normal maps for detail.

- LOD3+ (Very Low-Poly / Imposter): For cars at extreme distances or in large crowds. Can be as low as 1,000-5,000 polygons, or even a 2D impostor sprite.

Game engines automatically switch between these LODs based on the camera’s distance to the object, ensuring that only the necessary level of detail is rendered. Tools within 3ds Max, Blender, Maya, and directly in Unity/Unreal Engine (e.g., automatic LOD generation tools) assist in this process. When creating LODs, it’s crucial to maintain consistent UVs across all levels to prevent texture popping and ensure smooth transitions. Additionally, baking normal maps from the high-poly model to the lower-poly LODs helps retain crucial surface detail without increasing vertex count. When sourcing game-ready 3D car models, ensure they come with pre-configured LODs and optimized meshes.

Efficient Texture and Material Pipelines for Game Assets

Beyond polygon count, texture and material efficiency are critical for game performance. Excessive texture memory usage and high draw calls can severely impact frame rates.

- Texture Atlasing: Instead of using multiple small textures for different parts of the car, combine them into one larger texture map (an atlas). For example, all interior textures could be on one 4K atlas, and exterior textures on another. This reduces the number of texture lookups and significantly lowers draw calls, as the engine only needs to bind one material and texture set for multiple meshes.

- Material Instances: Most game engines allow for material instancing. This means you create a master material with all the shader logic, and then create instances of that material where you can change parameters (like color or roughness) without creating a completely new material. This saves on memory and processing overhead. For example, a single car paint master material can be instanced multiple times for different car colors.

- Texture Resolutions: Be pragmatic with texture resolutions. While 4K or 8K textures might be used for main body parts, smaller details like bolts or interior buttons can often use 512px or 256px textures. Optimizing individual texture sizes based on their screen space coverage is a common practice.

- Shader Complexity: Keep shader networks as simple as possible. Avoid overly complex nodes or excessive math operations that can tax the GPU. Using optimized PBR shaders provided by the game engine is generally a good starting point.

- Mesh Instancing: If multiple identical cars (e.g., parked cars in a city) are present, use mesh instancing where possible. The engine renders multiple copies of the same mesh using a single draw call, drastically improving performance.

These strategies collectively ensure that the 3D car models not only look great but also perform optimally in real-time interactive environments, delivering a fluid and immersive user experience.

Beyond the Screen: 3D Car Models in AR/VR and 3D Printing

The utility of high-quality 3D car models extends far beyond traditional rendering and game development. With the advent of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), and the increasing accessibility of 3D printing, these digital assets are finding new and exciting applications. From interactive car configurators that allow customers to explore vehicles in a virtual showroom to precise physical prototypes used in design validation, 3D car models are becoming indispensable tools in various industries. However, each of these emerging technologies presents its own unique set of requirements and optimization challenges.

For AR/VR, the emphasis shifts to extreme performance optimization and highly immersive, real-time interactivity. For 3D printing, the focus is on mesh integrity, watertightness, and physical accuracy. Understanding how to prepare and optimize your 3D car models for these diverse applications ensures versatility and maximizes their value. Platforms like 88cars3d.com provide models often already prepared with common file formats like GLB and USDZ, which are essential for AR/VR deployment.

Tailoring Models for Immersive AR/VR Experiences

AR and VR experiences demand incredibly efficient 3D assets due to the high frame rates (typically 60-90 FPS per eye) required to prevent motion sickness and ensure immersion. This means even more stringent polycount budgets than traditional games, often targeting 30,000-80,000 polygons for an entire car, including interior, for a comfortable VR experience.

- Polycount and Draw Calls: Aggressive LOD implementation and texture atlasing are even more critical. Each draw call and vertex adds overhead, so consolidating materials and meshes is paramount.

- Optimized PBR Materials: While PBR is standard, complex shader networks can be too heavy for mobile AR or standalone VR headsets. Simpler, highly optimized PBR shaders are preferred, often using baked lighting (lightmaps) to offload real-time calculations.

- File Formats: Universal formats like GLB (Binary glTF) and USDZ are becoming the go-to for AR/VR. GLB is excellent for web-based AR/VR, bundling geometry, materials, textures, and animations into a single file. USDZ, developed by Apple, is optimized for AR on iOS devices and often features highly compressed textures and meshes.

- Interaction and Animation: AR/VR often requires interactive elements. Ensuring that doors, wheels, or hoods are separate, pivot-correct meshes allows for dynamic interaction. Simple, performance-friendly animations (e.g., opening doors) should be baked or driven by lightweight scripts.

- Baked Lighting: For static environments or less dynamic objects, baking lighting into textures (lightmaps) can drastically reduce real-time lighting calculations, freeing up GPU resources for more complex models or effects.

Testing performance on target hardware (e.g., Oculus Quest, iPhone ARKit) is crucial during development to ensure a smooth and responsive experience.

Preparing 3D Car Models for Accurate 3D Printing

3D printing requires an entirely different approach to mesh preparation compared to digital rendering. The primary concern is creating a watertight, manifold mesh that accurately translates into a physical object.

- Watertight Mesh: The model must be a single, closed volume without any holes, inverted faces, or intersecting geometry. Imagine filling it with water – no leaks allowed! This often means cleaning up any interior geometry not intended for printing (e.g., complex internal components that won’t be visible or print well).

- Wall Thickness: Ensure that all parts of the model have sufficient wall thickness to be physically printable. Thin walls can break easily or might not be recognized by the printer. A minimum thickness (e.g., 0.8mm – 2mm, depending on the material and printer) is often recommended.

- Mesh Repair and Optimization: Tools like Blender’s 3D Print Toolbox, MeshMixer, or Netfabb are invaluable for identifying and repairing non-manifold edges, open boundaries, and self-intersecting faces. Boolean operations, while useful, must be handled carefully to avoid creating messy geometry that needs extensive cleanup.

- Scale and Orientation: The model must be correctly scaled to the desired print size (e.g., 1:18, 1:24 scale). Orientation on the print bed also matters for minimizing support structures and optimizing print quality.

- File Formats: Common file formats for 3D printing include STL (Stereolithography), OBJ, and 3MF. STL is the most widely supported, but OBJ can carry color and material information (though not always used for single-material prints).

For detailed car models, it’s often necessary to separate components (e.g., body, wheels, interior) for individual printing and later assembly, especially if different materials or colors are desired. This modular approach can simplify the printing process and improve the final quality of the physical model. High-quality 3D models suitable for 3D printing often require specific preparation and quality checks to ensure manufacturability.

The Final Polish: Lighting, Environments, and Post-Processing

With a meticulously modeled, UV-mapped, textured, and optimized 3D car model, the final stages of rendering involve creating a compelling visual narrative through expert lighting, realistic environment integration, and sophisticated post-processing. These elements transform a technically sound asset into an evocative image or animation that captures attention and conveys emotion. Just as a professional photographer carefully sets up their studio or selects the perfect outdoor location, a 3D artist must master the interplay of light and shadow, the subtleties of environmental reflections, and the power of post-production to achieve truly stunning results.

Lighting is paramount, defining the mood, highlighting design features, and revealing material properties. The environment provides context and realistic reflections, grounding the car in its scene. Finally, post-processing techniques add the finishing touches, mimicking real-world camera effects and correcting any minor imperfections. This holistic approach to the final output ensures that every render of your 3D car model achieves its maximum visual impact.

Mastering Lighting: Studio, HDRI, and Physical Sky Systems

Effective lighting is the single most important factor in achieving photorealistic renders. Different lighting setups serve different purposes:

- Studio Lighting: Often used for product shots and advertising, studio lighting emphasizes the car’s form and reflections without environmental distractions. A typical setup involves a key light (main light source), fill lights (to soften shadows), rim lights (to define edges), and often large softboxes or area lights. HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image) studio environments can also be used, providing soft, even illumination and complex reflections from a single texture.

- HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image) Environments: These 360-degree panoramic images capture real-world light information, including color, intensity, and direction. Using an HDRI as a light source and reflection map is an incredibly efficient way to achieve realistic environmental lighting and reflections, instantly grounding your car in a believable space (e.g., a city street, a forest, a desert). You can rotate the HDRI to find the most flattering lighting and reflections.

- Physical Sky Systems: Many renderers offer procedural physical sky and sun systems. These simulate the real-world properties of the sun, sky, and atmosphere, allowing you to control time of day, cloud cover, and atmospheric turbidity. They are excellent for outdoor scenes where dynamic lighting changes (e.g., sunrise to sunset) are desired, offering highly realistic shadows and natural color gradients.

A common technique is to combine an HDRI for primary lighting and reflections with additional targeted area lights or spotlights to accentuate specific features, add kickers, or brighten shadowed areas. Understanding how light interacts with the car’s metallic paint and reflective surfaces is crucial for making it pop.

Enhancing Visuals through Post-Production and Compositing

Even the best raw render can be significantly improved through post-production and compositing. This stage mimics the processes used by professional photographers and filmmakers, adding a final layer of artistry and polish:

- Color Grading: Adjusting the overall color balance, saturation, contrast, and tone of the image to set a mood or match a specific aesthetic. Tools like curves, levels, and color balance are essential here.

- Bloom and Glare: Adding subtle glow effects around bright light sources (like headlights or reflections) to enhance realism. This is often done using a bloom filter, which can be controlled based on the intensity of the light in the render.

- Lens Flares: While often overused, tastefully applied lens flares can add a cinematic touch, especially in scenes with direct light sources hitting the camera.

- Depth of Field (DoF): Simulating the optical effect of camera lenses, where objects outside a certain focal range appear blurred. This helps draw the viewer’s eye to the main subject (the car) and adds a sense of photographic realism. The Z-depth render pass is crucial for accurately applying DoF in post-production.

- Chromatic Aberration: A subtle optical effect where colors separate slightly at the edges of objects, particularly noticeable in high-contrast areas. Applying a very slight amount can enhance realism.

- Vignetting: A subtle darkening of the image edges, which can help frame the subject and draw focus to the center.

- Adding Environment Elements: Compositing allows you to add elements like dust, smoke, lens dirt, or even subtle atmospheric haze to further integrate the car into its environment.

By leveraging render passes (as discussed earlier) in compositing software, artists gain granular control over every aspect of the final image. This non-destructive workflow provides immense creative freedom and is a hallmark of professional automotive visualization.

Conclusion

The journey from a blank canvas to a fully realized, high-quality 3D car model is a testament to technical skill, artistic vision, and meticulous attention to detail. We’ve explored the critical stages, from establishing flawless topology and strategic UV mapping to crafting advanced PBR materials and executing photorealistic rendering workflows. We’ve also delved into the crucial considerations for optimizing models for real-time game engines, preparing them for immersive AR/VR experiences, and ensuring their integrity for accurate 3D printing. Each step, from polycount management to texture atlasing and render pass compositing, plays an indispensable role in creating compelling automotive visuals.

Mastering these techniques requires practice, patience, and a continuous desire to learn and adapt to new technologies. The principles discussed here form the bedrock for creating versatile and impactful 3D car models that can excel across diverse applications – from the most demanding cinematic productions to the fastest-paced interactive simulations. Investing in high-quality starting assets can significantly streamline your workflow. When you’re ready to elevate your projects, consider platforms that prioritize precision and fidelity. For professionals seeking top-tier assets, 88cars3d.com offers a curated selection of 3D car models, meticulously crafted with clean topology, realistic PBR materials, and optimized for various pipelines, providing the perfect foundation for your next masterpiece. Embrace the challenge, apply these best practices, and watch your automotive visualizations truly shine.

Featured 3D Car Models

Nissan Micra 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Nissan Micra 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Eclipse GT 2001 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Eclipse GT 2001 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

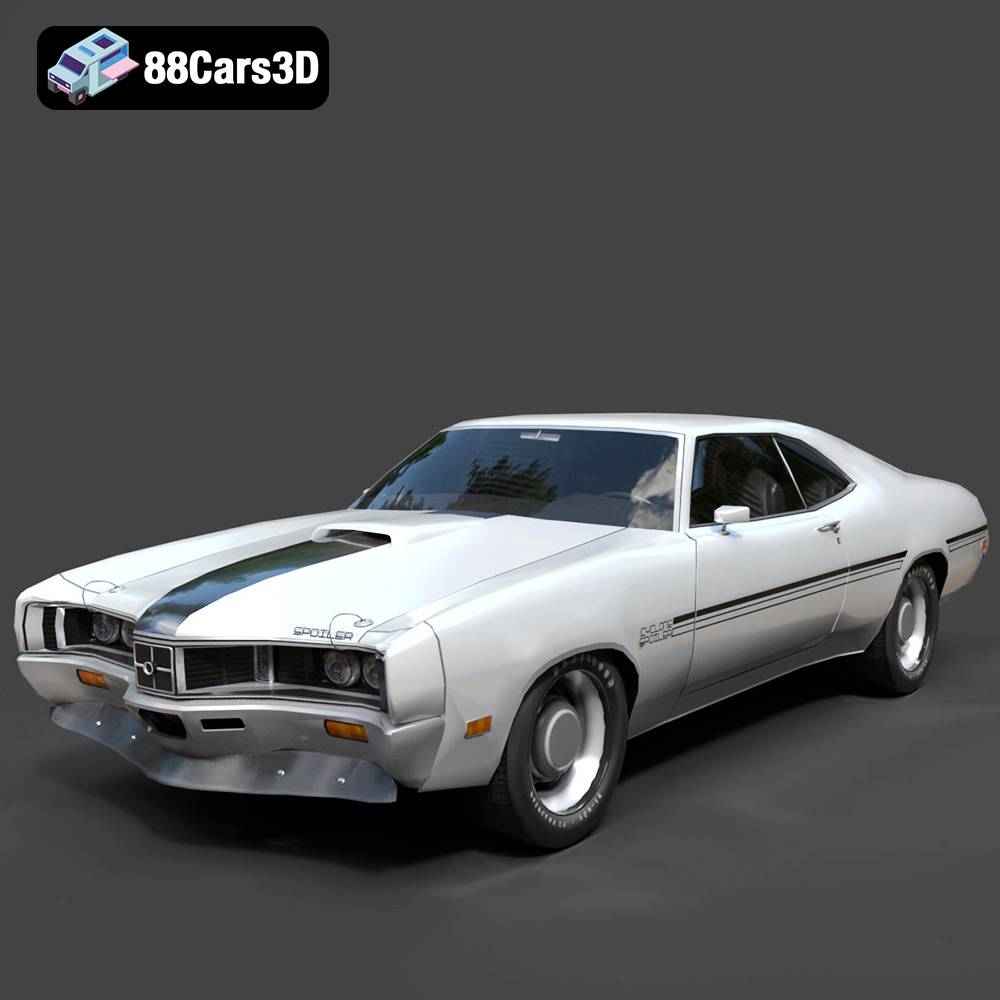

Mercury Cyclone Spoiler 1970 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercury Cyclone Spoiler 1970 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Opel Astra 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Opel Astra 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VIII 2003 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VIII 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Peugeot 307 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Peugeot 307 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Peugeot 207 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Peugeot 207 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VI 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VI 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Nissan Moco 007 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Nissan Moco 007 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99