From Polygon to Photorealism: The Ultimate Technical Guide to Using 3D Car Models

From Polygon to Photorealism: The Ultimate Technical Guide to Using 3D Car Models

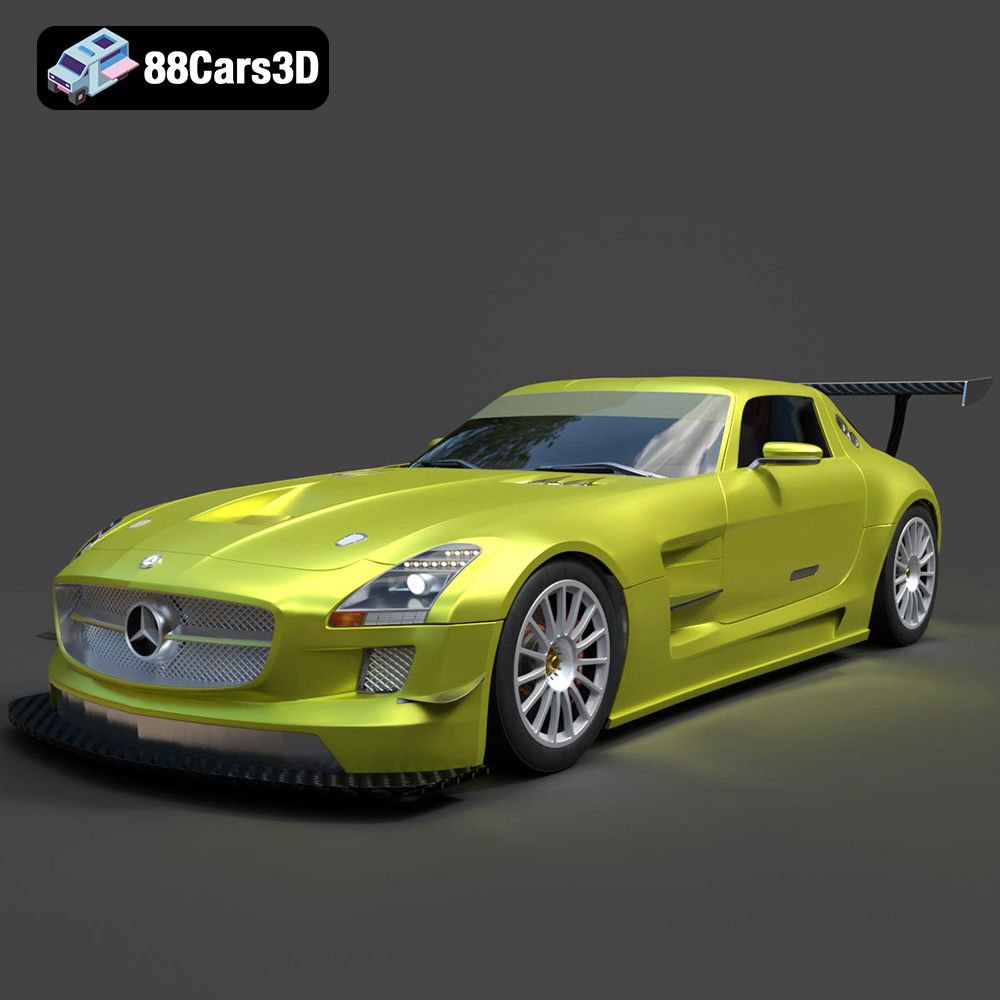

There’s an undeniable magic to a perfectly rendered automobile. The way light glints off a curved fender, the intricate detail of a headlight assembly, the subtle texture of leather on the interior—these elements combine to create images and experiences that are often indistinguishable from reality. But achieving this level of quality is more than just downloading a file and hitting “render.” It’s a complex process rooted in a deep understanding of 3D modeling fundamentals, material science, and rendering theory. For professionals in architectural visualization, advertising, and game development, the quality of the initial 3D car models is the bedrock upon which everything else is built.

This comprehensive guide will pull back the curtain on what separates an amateur model from a production-ready digital asset. We will dissect the critical technical components—from the invisible wireframe to the final pixel—that every artist and developer needs to master. Whether you are creating stunning automotive rendering for a marketing campaign or integrating high-performance game assets into a real-time environment, this is your roadmap to excellence.

The Foundation: Why High-Quality Topology Matters

Before any textures are applied or lights are placed, a 3D model exists as a wireframe mesh—a collection of vertices, edges, and polygons. The arrangement of these polygons, known as topology, is arguably the most critical factor determining a model’s quality and usability. Flawless topology isn’t just about looks; it’s about function, ensuring predictable and clean results during texturing, shading, and animation.

Understanding Polygon Flow and Density

Polygon flow refers to the direction in which the edge loops of a model are organized. In automotive modeling, clean polygon flow is paramount. The edge loops should follow the natural contours and lines of the vehicle’s bodywork. For example, edge loops should crisply define the wheel arches, run parallel along the sharp crease of a shoulder line, and cleanly encircle headlights and grilles. This ensures that when the model is subdivided or smoothed, the shapes hold their form and definition.

Polygon density is equally important. A model for a cinematic close-up might feature several million polygons to capture every minute detail. In contrast, a model for a real-time application will have a significantly lower polygon budget. High-quality models are often built with a “mid-poly” approach using subdivision-ready, all-quad geometry. This provides the flexibility to increase or decrease the density as needed for the specific application without fundamentally altering the model’s structure.

The Impact of Topology on Shading and Reflections

This is where poor topology reveals itself most dramatically. A car’s surface is essentially a mirror, and any imperfection in the underlying mesh will cause distracting artifacts in the reflections. Triangles, ngons (polygons with more than four sides), and poorly spaced edge loops create pinching and surface tension, leading to visible wobbles and distortions in the highlights. A clean, evenly-spaced grid of quadrilaterals allows the surface normals to be calculated correctly, resulting in the smooth, liquid-like reflections that define a photorealistic car render. When evaluating a model, always inspect the wireframe under a glossy material to see how it handles highlights.

What to Look for When Evaluating a Wireframe

When you acquire a professional 3D car model, the first thing you should do is inspect its wireframe. Look for these key indicators of quality:

- All-Quad Geometry: The vast majority of the model, especially the visible body panels, should be composed of four-sided polygons (quads).

- Even Spacing: Polygons should be distributed evenly across surfaces, with higher density only in areas of high curvature or detail.

- Clean Edge Loops: Supporting edge loops should be used to define sharp edges and panel gaps, preventing pinching when a subdivision modifier (like TurboSmooth in 3ds Max or a Subdivision Surface in Blender) is applied.

- No Isolated Vertices or Ngons: These are red flags that indicate a sloppy or broken model that will cause significant shading and texturing problems.

UV Unwrapping: The Blueprint for Detailed Textures

If topology is the skeleton of a 3D model, UVs are its skin. A UV map is the 2D representation of the 3D model’s surface, acting as a guide for how textures are applied. For complex objects like vehicles, a well-executed UV unwrap is non-negotiable for achieving realistic detail.

Core Principles of Automotive UVs

Professional UV unwrapping for a vehicle follows several core principles. First is minimizing distortion; the UV shells (the individual unwrapped pieces) should be laid out with as little stretching or compressing as possible. This is often checked using a UV checkerboard pattern. Second, seams should be placed logically and in areas of low visibility, such as along panel gaps, on the underside of the car, or on the inside of the wheel wells. Third, texel density—the amount of texture resolution per unit of surface area—should be consistent across the model, or intentionally higher for areas that will be seen up close, like badges or wheel rims.

Multi-Tile UV Workflows (UDIMs)

To achieve the incredibly high resolution required for 4K or 8K rendering, a single UV map is often insufficient. This is where the UDIM (U-Dimension) workflow comes in. UDIMs allow an artist to spread a model’s UVs across multiple texture sets, or “tiles.” For a car, this is incredibly powerful. The main body can be on one UDIM tile, the interior on another, the wheels on a third, and so on. This workflow, standard in visual effects and high-end rendering, allows for massive texture resolutions (e.g., multiple 8K maps) to be applied to a single object without performance degradation in the viewport, ensuring every screw head and stitch is perfectly crisp.

Checking UVs Before You Begin Texturing

Always perform a quality check on a model’s UVs. Apply a simple checkerboard texture and look for areas where the squares are stretched, squashed, or skewed. Pay close attention to how the pattern flows across seams; it should be as continuous as possible. Check for any overlapping UV shells, as this will cause textures to bake or render incorrectly. A professional model from a reputable source like 88cars3d.com will have clean, non-overlapping, and logically laid-out UVs ready for production.

Material and Texture Creation for Peak Realism

With a solid foundation of topology and UVs, the next step is breathing life into the model with materials and textures. Modern workflows rely on Physically Based Rendering (PBR), a methodology that seeks to simulate the properties of light and materials as they behave in the real world.

The PBR (Physically Based Rendering) Workflow

The PBR workflow primarily uses a set of texture maps to define a material’s properties. For a vehicle, the most important maps are:

- Albedo/Base Color: This defines the raw color of the surface, free of any lighting or shadow information.

- Roughness/Glossiness: This is the most crucial map for realism. It controls how rough or smooth a surface is, which dictates whether reflections are sharp and mirror-like (low roughness, like chrome) or diffuse and broad (high roughness, like tire rubber).

- Metallic: This map tells the shader whether a surface is a metal or a non-metal (dielectric). It’s typically a black and white map, where 1 (white) is fully metallic and 0 (black) is non-metallic.

- Normal/Bump: This map adds fine surface detail, like the grain of leather or the pattern of carbon fiber, without adding any extra polygons.

Crafting a Believable Car Paint Shader

Car paint is one of the most complex materials to replicate digitally. It’s not a single layer but a composite of multiple layers. A high-quality car paint shader in 3ds Max (using V-Ray or Corona) or Blender (using Cycles) will typically involve a layered approach:

- Base Coat: This is the underlying layer, which might include subtle metallic flakes controlled by a noise or procedural texture.

- Pigment Layer: The primary color of the paint.

- Clear Coat Layer: A top, highly reflective layer that simulates the protective varnish on a real car. This layer has its own roughness value (usually very low) and is controlled by a Fresnel effect, making reflections more prominent at glancing angles. This clear coat is what gives car paint its characteristic depth and glossy finish.

Detailing Beyond the Paint

A car is more than just painted metal. To achieve photorealism, every material must be considered. Tires require a high-roughness material with subtle dirt maps and a normal map for the sidewall lettering. Glass needs proper Index of Refraction (IOR) settings (around 1.52) and subtle grime or dust textures. Chrome trim should be fully metallic with very low roughness. Brake discs often feature anisotropic reflections (reflections that stretch in a specific direction) to simulate the brushed metal finish. These details accumulate to sell the final image as real.

Optimizing 3D Car Models for Real-Time Game Engines

Using 3D car models for real-time applications like Unreal Engine or Unity presents a different set of challenges. Here, performance is king. The goal is to maintain the highest possible visual fidelity while ensuring the game runs at a smooth frame rate.

The LOD (Level of Detail) Strategy

The single most important optimization for game assets is the use of LODs. An LOD system uses multiple versions of the same model at varying polygon counts. The highest resolution version, LOD0, is shown when the player is close to the car. As the car moves further away, the engine automatically swaps to lower-resolution versions (LOD1, LOD2, LOD3), which are invisible to the player but drastically reduce the number of polygons the GPU has to render. A hero car in a modern racing game might have a LOD0 of 200,000-500,000 triangles, while its final LOD might be just a few hundred.

Poly Count Budgets and Draw Call Management

Game developers work within strict budgets. Every polygon and every material adds to the computational load. Models must be carefully optimized to remove any unseen polygons (like engine parts in a car with a sealed hood). Furthermore, each material applied to an object typically results in a “draw call,” which is an instruction to the GPU. To minimize draw calls, artists often use texture atlasing—the practice of combining textures for multiple parts (e.g., the dashboard, steering wheel, and seats) into a single, larger texture map. This allows multiple objects to be rendered with a single material, significantly improving performance.

Real-Time Shaders in Unreal Engine

Game engines like Unreal Engine have dedicated shaders optimized for real-time performance. Unreal’s Automotive Materials pack, for instance, provides a highly advanced car paint shader that simulates metallic flakes and a clear coat layer, but is designed to run efficiently in real-time. The texturing workflow is also optimized. It’s common practice to “channel pack” PBR textures. For example, the Roughness, Metallic, and Ambient Occlusion maps (all grayscale) can be packed into the Red, Green, and Blue channels of a single texture file, saving memory and improving shader efficiency.

A Practical Workflow: Creating a High-End Automotive Rendering

Let’s tie these concepts together with a real-world case study: creating a studio render for a car advertisement.

Step 1: Asset Selection and Preparation

The process begins by selecting a top-tier asset. We would source a model known for its clean topology and high-resolution UDIM-based textures, such as those available from a specialized marketplace like 88cars3d.com. Upon importing the model into our chosen software (e.g., Blender), we would first do a quick check of the wireframe and UVs to confirm everything is production-ready.

Step 2: Scene Setup and Lighting

For a studio shot, lighting is everything. We would set up a simple ground plane and use a high-quality HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image) of a photography studio to provide realistic, image-based lighting and reflections. This immediately grounds the car in a believable space. To add drama and define the car’s lines, we would add several large, soft area lights, carefully placing them to create long, elegant highlights along the bodywork. A key light, fill light, and rim light would complete the setup.

Step 3: Material Refinement and Final Render

Even with great textures, materials often need tweaking to suit the specific lighting environment. We might adjust the roughness of the clear coat on the car paint shader to get the perfect reflection sharpness, or add a subtle procedural noise to the tire’s roughness map to break up the uniformity. Once we are happy with the look, we would set up our final render camera, perhaps using a long focal length (e.g., 85mm) to compress the perspective and add a slight depth-of-field effect. The final render would be done at high resolution (e.g., 6K) with enough samples to eliminate noise, likely rendered as a multi-pass EXR file for maximum flexibility in post-production.

Conclusion: Quality In, Quality Out

From the precise flow of polygons across a body panel to the complex interplay of light on a multi-layered paint shader, the creation of world-class digital vehicles is a discipline of technical artistry. Whether your final destination is a photorealistic print ad or a high-octane racing game, the principles remain the same: a successful project is always built on a foundation of a technically excellent 3D model.

Understanding topology, UVs, PBR materials, and application-specific optimization is what empowers you to push the boundaries of realism and performance. By investing in high-quality assets and mastering these core concepts, you move beyond simply using 3D car models and begin the true work of crafting unforgettable digital experiences. For professionals who demand precision and reliability from the very start, sourcing assets from curated platforms like 88cars3d.com can be the critical first step in a successful and efficient production pipeline.