Beyond the Showroom: A Technical Guide to 3D Car Models for Rendering and Game Development

Beyond the Showroom: A Technical Guide to 3D Car Models for Rendering and Game Development

From the hyper-realistic reflections in a cinematic car chase to the customizable vehicle in your favorite racing game, 3D car models are a cornerstone of modern digital media. They are more than just digital replicas; they are complex, multi-layered assets engineered for specific purposes. Creating a convincing digital vehicle is an intricate blend of artistry and technical precision. A model destined for a photorealistic automotive rendering has vastly different requirements than one built to perform smoothly as a real-time game asset. Understanding these differences is crucial for any artist, developer, or designer looking to achieve professional results.

This comprehensive guide will demystify the technical complexities behind high-quality 3D car models. We will dissect their anatomy, explore professional workflows for both cinematic rendering and interactive game development, and examine real-world case studies. Whether you are a seasoned 3D artist looking to refine your automotive workflow or a game developer searching for the perfect vehicle asset, this deep dive will equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions and elevate your projects to the next level.

The Anatomy of a High-Quality 3D Car Model

Before a 3D car can grace the screen, it begins as a collection of polygons, textures, and data. The quality of this foundational asset dictates the potential of the final output. A poorly constructed model will fight you at every step, while a professionally crafted one provides a flexible and robust canvas for your creative vision.

Topology, Edge Flow, and Polygon Count

At its core, a 3D model is a mesh of vertices, edges, and faces (polygons). The arrangement of these polygons, known as topology, is paramount for a clean and predictable result. For automotive models, good topology means:

- Quad-Dominant Geometry: The mesh should be primarily composed of four-sided polygons (quads). Quads subdivide cleanly and are easier to UV unwrap, making them ideal for high-detail “hero” assets used in automotive rendering. Triangles (tris) are acceptable, especially after conversion for a game engine, but they can cause pinching and artifacts during subdivision modeling.

- Logical Edge Flow: The edges should follow the natural contours and curves of the car’s body panels. This ensures that when the model is subdivided (smoothed), it holds its shape perfectly without creating bumps or dents. Proper edge flow is especially critical around curved areas like wheel arches and headlight housings.

- Appropriate Polygon Count: There is no single “correct” poly count; it is entirely context-dependent. A high-poly model for a close-up 4K render might have millions of polygons to capture every minute detail. In contrast, a low-poly model for a mobile game might be under 50,000 polygons to ensure smooth performance. Professional models are often provided in multiple formats or with a clean enough topology that they can be easily optimized.

UV Unwrapping and PBR Texturing

If the 3D mesh is the car’s body, the textures are its paint, chrome, and leather. To apply these textures correctly, the 3D model must be “unwrapped” into a 2D layout, a process called UV mapping.

- Clean and Non-Overlapping UVs: For a unique paint job or decal placement, the UV shells (the unwrapped pieces of the model) must be laid out cleanly in the 0-1 UV space without overlapping. This allows for precise texture painting. For tiling materials like carbon fiber or leather grain, some overlapping UVs can be an efficient optimization.

- Physically Based Rendering (PBR): The modern standard for texturing, PBR aims to simulate how light behaves in the real world. A PBR workflow uses several texture maps to define a material’s properties:

- Albedo/Base Color: The pure color of the surface, without any lighting or shadow information.

- Roughness/Glossiness: Controls how rough or smooth a surface is, which dictates whether reflections are sharp (like chrome) or diffuse (like a tire wall).

- Metallic: A black-and-white map that tells the shader if a surface is a metal or a non-metal (dielectric).

- Normal Map: Adds fine surface detail (like leather grain or grille mesh) without adding extra polygons.

Model Hierarchy and Separated Components

A high-quality 3D car model is not a single, monolithic object. It should be a logically organized collection of distinct parts. A proper hierarchy means that the wheels, doors, hood, trunk, and steering wheel are all separate objects, correctly named and grouped. The pivot points for these objects should be placed accurately to allow for realistic animation—a door’s pivot should be at its hinge, and a wheel’s pivot should be at its center axle. This separation is non-negotiable for interactive applications like games or car configurators.

Workflow Deep Dive: From Model to Photorealistic Automotive Rendering

The goal of automotive rendering is often to create an image that is indistinguishable from a real photograph. This pursuit of realism requires high-detail models, sophisticated lighting, and meticulous material creation. Here, we’ll focus on a common workflow using 3ds Max and V-Ray/Corona.

Setting the Scene in 3ds Max

Once you have a high-polygon 3D car model, the first step is to create a virtual photo studio. The environment is just as important as the model itself in achieving realism.

- Import and Preparation: Import your model (often in .FBX or .MAX format). Check the scale to ensure it matches real-world units (e.g., centimeters or inches). This is crucial for lighting and depth-of-field effects to behave realistically.

- Studio Lighting with HDRI: The fastest way to achieve realistic lighting and reflections is with a High Dynamic Range Image (HDRI). This is a 360-degree panoramic image that contains a vast range of light intensity data. Applied to a dome light in V-Ray or Corona, it instantly surrounds your car with realistic environmental light and provides the complex, nuanced reflections that make a car’s surface come alive.

- Refinement with Area Lights: While an HDRI provides a great base, professional renders often use additional area lights to act as “softboxes” or “key lights.” These are used to sculpt the car’s form, create beautiful specular highlights along its body lines, and separate it from the background.

Material Mastery for Automotive Surfaces

Creating believable materials is where a render truly shines. A car is a collection of diverse and complex surfaces, and each requires a specific approach.

- Complex Car Paint: A realistic car paint shader is not a single color. It’s a multi-layered material. In V-Ray or Corona, this is often built using a blend material or a dedicated car paint shader. It typically consists of:

- A base layer for the primary color.

- A “flakes” layer with a procedural noise map to simulate metallic flecks, often with its own unique color and orientation.

- A “clear coat” layer on top with its own reflectivity and a slight “orange peel” effect applied via a noise map in the bump slot.

- Glass and Chrome: Windshields and windows require a material with high refraction and reflection. Small details like a slight tint color and subtle surface imperfections can add a layer of realism. Chrome is simpler: a highly reflective material with a very low roughness value and a high metallic value.

- Tires and Plastics: Tires are a dark, dielectric material with high roughness. The sidewall details (lettering) can be added using a normal map or displacement map. Trim plastics vary from matte and rough to satin and slightly reflective. Using reference photos is key to dialing in these values correctly.

Optimizing 3D Car Models for Real-Time Game Engines

Creating a 3D car model for a game is a battle between visual fidelity and performance. The goal is to make the car look as good as possible while maintaining a high and stable frame rate. The workflow for creating game assets is fundamentally about optimization.

The Art of Retopology and LODs

A multi-million polygon model from a cinematic render would bring any game engine to its knees. The solution is retopology: creating a new, clean, low-poly mesh that sits on top of the original high-poly model.

- Manual vs. Automatic Retopology: While tools exist for automatic retopology, for a hero game asset like a player vehicle, manual retopology in Blender or 3ds Max yields the best results. It allows an artist to control the edge flow precisely, ensuring the car’s silhouette is preserved and that it deforms predictably if damaged.

- Level of Detail (LODs): Game engines use a system called Level of Detail (LODs) to further optimize performance. This involves creating multiple versions of the car model, each with a progressively lower polygon count. The game engine automatically swaps these models based on the car’s distance from the camera. LOD0 is the highest detail model seen up close, while LOD3 might be a very simple shape seen from hundreds of meters away.

Baking High-Poly Details onto Low-Poly Meshes

How does a low-poly model look so detailed? The magic is in texture baking. This process projects the surface details from the high-poly model onto the texture maps of the low-poly model.

- Normal Map Baking: This is the most critical bake. It captures all the fine surface changes, panel gaps, and small details from the high-poly mesh and encodes them into a normal map. When this map is applied to the low-poly model in the game engine, it creates the illusion of high-resolution detail by manipulating how light reflects off the surface.

- Ambient Occlusion (AO) Baking: An AO map pre-calculates the small, soft contact shadows in crevices and areas where objects are close together (e.g., where a door panel meets the car body). This adds depth and a sense of grounding to the model.

Unreal Engine 5 Integration

Getting the optimized game asset into an engine like Unreal Engine 5 involves a few key steps.

- Importing the FBX: The car model, including its LODs and skeleton (if rigged), is typically exported as a single .FBX file. During import into Unreal, you’ll set up the materials and assign the PBR textures baked earlier.

- Material Instancing: To allow for easy customization (like changing the car’s color), materials are set up with parameters exposed. This allows developers to create “Material Instances” where they can change the base color, roughness, or metallic values without having to create an entirely new material, which is highly efficient.

- Vehicle Physics Setup: Unreal Engine’s Chaos Vehicle system allows you to add realistic physics. This involves setting up a vehicle blueprint, assigning collision shapes to the chassis and wheels, and tuning parameters like engine torque, suspension, and tire friction to achieve the desired handling.

Case Study: Creating a Cinematic Car Chase Sequence

Imagine a project that requires a short, dynamic car chase for a film or advertisement. The focus is on visual storytelling and realism, with no real-time performance constraints.

Pre-Production and Asset Selection

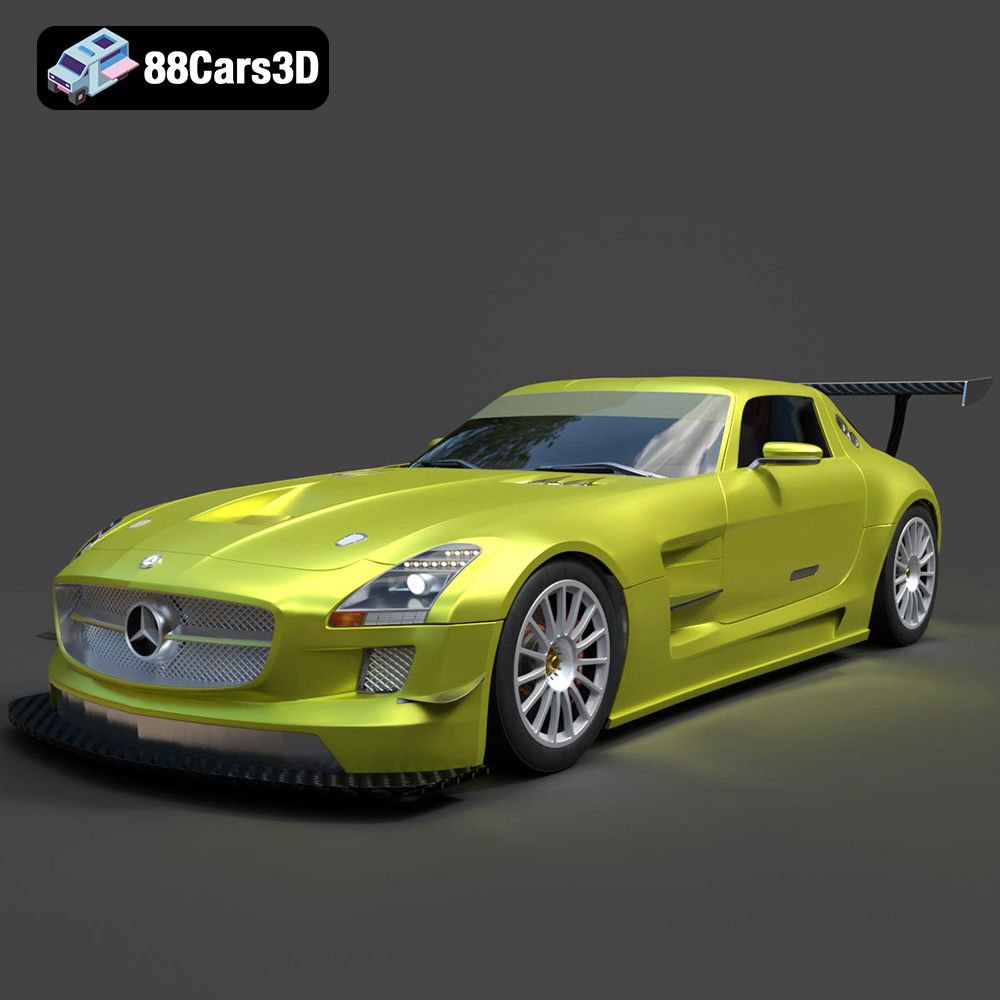

The first step is selecting the right hero cars. Building a photorealistic car from scratch can take hundreds of hours. This is where a marketplace for professional 3D car models like **88cars3d.com** becomes invaluable. For this use case, you would look for a model with a very high polygon count, detailed interior, clean topology for smooth reflections, and high-resolution PBR textures. The model must be accurate and well-crafted, as every detail will be scrutinized in close-up shots.

Scene Assembly and Animation in Blender

Using a tool like Blender with its Cycles render engine, the artist would assemble the scene. This involves building or acquiring a 3D environment (e.g., a city street), setting up the HDRI and key lights, and importing the car models. The cars would then be animated, often by constraining them to follow a path (a curve object). The camera work is crucial, using dynamic shots with realistic camera shake and focal lengths to create a sense of speed and intensity.

Rendering and Compositing for a Film Look

The sequence is rendered out frame by frame, often in multiple passes (e.g., beauty, reflection, shadow). These passes are then brought into a compositing program like Adobe After Effects or Blackmagic Fusion. Here, the final touches are added: motion blur to enhance the sense of speed, depth of field to guide the viewer’s eye, lens flares, and final color grading to achieve a specific cinematic mood. This layered approach provides maximum control over the final image.

Conclusion: The Right Model for the Right Job

The journey from a blank viewport to a stunning digital vehicle is a testament to technical skill and artistic vision. We’ve seen that the path diverges significantly depending on the final destination: the controlled, perfection-driven world of automotive rendering or the optimized, performance-critical realm of real-time game assets.

For rendering, success hinges on high-fidelity models with immaculate topology, complex multi-layered materials, and sophisticated lighting. For game development, the focus shifts to clever optimization through retopology, detail baking, and efficient engine integration. Regardless of the path, one truth remains constant: the quality of the foundational 3D car model is the single most important factor. Starting with a professionally crafted asset, like the meticulously detailed vehicles found on marketplaces such as **88cars3d.com**, saves countless hours and provides the robust, flexible foundation needed to bring any creative vision to life. By understanding the technical requirements of your project, you can choose the right tool for the job and accelerate your journey from concept to reality.