The Foundation: Flawless 3D Car Model Topology and Edge Flow

The sleek lines, the polished gleam, the intricate details – a high-quality 3D car model is more than just a digital asset; it’s a testament to precision, artistry, and technical mastery. From the adrenaline-pumping realism of modern video games to the meticulous precision of automotive design visualization, and the immersive experiences of AR/VR, 3D car models are central to countless digital applications. But what goes into crafting these masterpieces? It’s a journey through complex workflows, demanding software expertise, and an unwavering commitment to detail.

This comprehensive guide will take you on a deep dive into the technical intricacies behind creating, optimizing, and deploying 3D car models across various industries. We’ll explore the foundational principles of topology, demystify the art of UV mapping and PBR materials, unravel advanced rendering workflows, and uncover the critical optimization techniques for real-time environments like game engines and AR/VR. Whether you’re an aspiring 3D artist, a seasoned game developer, an automotive designer, or a visualization professional, understanding these technical pillars is essential for producing truly exceptional digital vehicles that not only look stunning but also perform flawlessly in their intended applications.

The Foundation: Flawless 3D Car Model Topology and Edge Flow

At the heart of every great 3D car model lies impeccable topology. Topology refers to the arrangement of vertices, edges, and faces that form the surface of your model. For automotive models, clean, quad-dominant topology is not merely a preference; it’s a fundamental requirement. It ensures smooth surfaces, predictable deformation (if animated), and compatibility with subdivision surface modifiers, which are crucial for achieving the refined curves and high-fidelity details expected in modern car renderings. Bad topology, on the other hand, can lead to pinching, artifacts, and a frustrating sculpting or texturing experience.

When modeling, artists must meticulously control the flow of edges to accurately define the car’s intricate curves and hard edges. This involves strategically placing edge loops to support sharp creases while allowing broader areas to remain smooth when subdivided. The goal is to achieve an efficient polygon count without sacrificing crucial details or surface integrity. For hero assets, polygon counts can range from 150,000 to over 500,000 triangles for a highly detailed interior and exterior, while game-ready assets will demand significantly lower counts, often relying on Normal Maps to convey detail.

N-gons, Triangles, and Quads: The Core Principles

In 3D modeling, faces are typically made up of three vertices (triangles) or four vertices (quads). Faces with more than four vertices are known as N-gons. For most modeling tasks, particularly in automotive design, a quad-dominant topology is the gold standard. Quads subdivide predictably and evenly, which is critical for creating the smooth, continuous surfaces characteristic of car bodies. When a mesh is subdivided (using modifiers like Turbosmooth in 3ds Max or Subdivision Surface in Blender), quads create a clean, flowing mesh. N-gons, conversely, can cause unpredictable shading, pinching artifacts, and issues during UV unwrapping and deformation. They should generally be avoided on visible surfaces.

While quads are king, triangles do have their place. They are often used in areas that will not deform, such as the interior of an engine block or in highly optimized game assets where every polygon counts, and the renderer triangulates everything anyway. Even then, an underlying quad-based mesh that is later triangulated offers better control and predictability during the modeling phase. Understanding when and where to use each type of face is crucial for maintaining a clean, robust model that can be easily edited, textured, and rendered without unexpected issues.

Achieving Perfect Edge Flow for Smooth Surfaces

Edge flow dictates how the edges on your model follow the contours of the surface. For a car, this means ensuring edge loops wrap around headlights, flow along door seams, and define the subtle curvature of fenders. Good edge flow is paramount for achieving smooth, appealing reflections on the car’s paintwork and for preventing “pinching” artifacts when subdivision surfaces are applied. To create sharp creases, such as those found around window frames or body panel gaps, support loops (additional edge loops placed very close to the primary edge) are essential. These loops help the subdivision algorithm “hold” the sharp edge without introducing unwanted smoothing.

Managing polygon density is another critical aspect. Areas with high curvature or intricate details will naturally require a higher density of polygons, while flatter surfaces can manage with fewer. The challenge lies in transitioning smoothly between these different densities using techniques like edge merging or carefully planned face reduction without disrupting the overall edge flow. Software like 3ds Max, Blender, and Maya offer powerful modeling tools for manipulating vertices and edges, enabling artists to meticulously craft the precise geometry required for photorealistic automotive assets. For instance, using tools like “Connect,” “Extrude Along Spline,” or “Edge Slide” can help maintain clean edge distribution and curvature.

Texturing for Realism: UV Mapping and PBR Materials

Once the geometric foundation is solid, the next crucial step is to give the 3D car model its surface characteristics – its paint, chrome, glass, and rubber. This involves two core processes: UV mapping and the creation of Physically Based Rendered (PBR) materials. These techniques transform a raw mesh into a visually rich and believable object, capable of reacting accurately to light in a virtual environment. Without precise UVs and well-calibrated PBR textures, even the most perfectly modeled car will look flat and artificial, failing to meet the high standards of modern visualization.

The texture resolutions used for a 3D car model can vary significantly based on its application. For high-end renderings, individual components like tires or car paint layers might use 4K (4096×4096) or even 8K textures. Game assets, on the other hand, might rely on a combination of 2K or 1K textures, often packed into atlases to conserve memory and optimize draw calls. The careful balance between visual fidelity and performance is a constant consideration, particularly when dealing with the many distinct material zones on a car.

Masterful UV Mapping for Automotive Assets

UV mapping is the process of flattening out the 3D surface of your model into 2D space, allowing a 2D image (texture map) to be applied to it. For automotive assets, meticulous UV unwrapping is critical. Seams, which are the edges where the 3D model is cut to be flattened, must be strategically placed in inconspicuous areas (e.g., along panel lines, under trim) to minimize visible texture stretching or discontinuities. Techniques like planar, cylindrical, and spherical mapping are often used for different parts of the car, followed by detailed manual adjustments to optimize the UV layout. A ‘checker map’ texture is an invaluable tool during this stage, helping artists identify and correct any stretching or distortion.

Efficient UV packing is also vital, especially for game assets or when using texture atlases. This involves arranging the UV islands (the flattened pieces of the model) within the 0-1 UV space as tightly as possible to maximize texture resolution and minimize wasted space. For extremely high-detail models, techniques like UDIMs (U-Dimension) can be employed. UDIMs allow artists to use multiple UV tiles (each with its own texture map) for a single mesh, which is common in film and high-end automotive visualization where multiple 4K or 8K textures might be needed for different body panels or intricate components. Software like Blender, 3ds Max, and Maya offer advanced UV editing toolsets, often supplemented by dedicated unwrapping solutions for complex surfaces.

Crafting Physically Based Rendered (PBR) Materials

PBR (Physically Based Rendering) is the modern standard for creating realistic materials. Unlike older workflows, PBR materials accurately simulate how light interacts with surfaces, resulting in predictable and consistent rendering across various lighting conditions. The two main PBR workflows are “Metallic-Roughness” and “Specular-Glossiness,” both relying on a set of texture maps to define a material’s properties. For cars, a typical PBR material setup includes:

- Albedo/Base Color Map: Defines the base color of the surface, stripped of any lighting information.

- Metallic Map: Indicates which parts of the surface are metallic (white) and which are dielectric (black).

- Roughness Map (or Glossiness Map): Controls the microsurface detail, dictating how rough or smooth the material is, which directly affects reflections.

- Normal Map: Adds fine surface detail (bumps, scratches, panel lines) without increasing polygon count.

- Ambient Occlusion (AO) Map: Simulates soft shadows where surfaces are close together, enhancing perceived depth.

- Displacement/Height Map: Physically displaces the mesh surface for true volumetric detail (used sparingly for performance reasons).

Creating realistic car paint is a complex PBR challenge, often involving multiple layers: a base color, a metallic flake layer, and a clear coat layer with its own roughness and normal properties. For tires, specific rubber PBR values, combined with detailed normal maps for tread patterns, are essential. Software like Substance Painter is a go-to for texturing PBR assets, offering powerful tools for procedural generation, hand-painting, and smart materials that accelerate the workflow. Additionally, node-based material editors within renderers like Corona, V-Ray, Cycles, and Arnold provide granular control over every aspect of a PBR shader network, allowing for highly customized and accurate material responses.

Bringing Cars to Life: Advanced Rendering Workflows

Once a 3D car model is meticulously modeled and textured with PBR materials, the final step in creating breathtaking visualizations is the rendering process. This stage involves setting up lighting, defining the environment, and fine-tuning renderer settings to produce photorealistic images or animations. Achieving a professional automotive render requires a deep understanding of light physics, camera principles, and the specific capabilities of your chosen rendering engine. The goal is to make the digital car indistinguishable from a real photograph, capturing its form, reflections, and material qualities with absolute fidelity.

Render times can vary wildly depending on the scene complexity, resolution, and chosen render engine. A single 4K image might take minutes to hours to render on a powerful workstation, while a full animation can require days or weeks on a render farm. Optimizing render settings involves balancing quality with performance, knowing which parameters to tweak for noise reduction, global illumination accuracy, and overall speed. When sourcing high-quality, pre-textured 3D car models, platforms like 88cars3d.com can significantly reduce the initial setup time, allowing artists to jump straight into lighting and rendering.

Lighting and Environment Setup for Automotive Shots

Lighting is arguably the most critical element in an automotive render. It dictates how the car’s form is perceived, how reflections play across its surface, and the overall mood of the image. For studio shots, common setups include:

- Three-Point Lighting: Key light, fill light, and back/rim light to define form.

- Softboxes and Strip Lights: Large, diffused light sources to create soft, flattering reflections on the car’s body.

- HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image): An omnidirectional photographic environment that provides both lighting and reflections, creating incredibly realistic ambient light and reflections. Many professional automotive renders start with a high-quality studio or outdoor HDRI map.

For outdoor scenes, physical sun and sky systems, often combined with an HDRI for environmental context, are used to simulate natural light. The placement and intensity of these lights, along with the color temperature, must be carefully considered to accurately replicate real-world conditions. Understanding how reflections interact with the car’s paint and chrome is paramount; the environment itself becomes part of the car’s visual appeal, reflecting in its glossy surfaces and revealing its form.

Renderer-Specific Strategies (Corona, V-Ray, Cycles, Arnold)

Different renderers offer unique strengths and workflows.

- Corona Renderer (3ds Max, Cinema 4D): Known for its ease of use, physically accurate light transport, and intuitive interactive rendering. It’s often favored for architectural and automotive visualization due to its fast setup and realistic results with minimal tweaking. Optimizing involves adjusting noise limits and light samples.

- V-Ray (3ds Max, Maya, SketchUp, Rhino): A production-proven workhorse, V-Ray offers immense control and flexibility. It excels in complex scenes and has powerful tools for volumetrics, caustics, and extensive render element output. Optimizations often involve careful management of GI settings (Brute Force/Light Cache) and sampling rates.

- Cycles (Blender): Blender’s integrated path tracer, Cycles, delivers impressive photorealistic results. Its node-based material system is powerful, and it benefits from GPU rendering. Optimizations include reducing light path bounces, using non-progressive sampling, and denoisers.

- Arnold (Maya, 3ds Max, Houdini): A robust, unbiased Monte Carlo path tracer, Arnold is widely used in film and TV for its high-quality, predictable results. It’s particularly strong with complex scenes, volumetrics, and fur/hair. Optimization typically involves adjusting sampling settings for individual lights and materials, and using AOVs (Arbitrary Output Variables) for compositing.

Regardless of the renderer, setting up render passes (also known as AOVs or Render Elements) is crucial for post-processing. These passes include beauty, alpha, reflection, refraction, diffuse, Z-depth, Ambient Occlusion, and Cryptomatte (for easy mask generation). These individual layers provide immense flexibility in compositing software like Adobe Photoshop or Foundry Nuke, allowing artists to fine-tune exposure, color, glow, and depth of field without re-rendering the entire scene.

Game-Ready Assets and Real-time Optimization

While cinematic renders aim for absolute photorealism without strict performance constraints, game development demands a different approach. Real-time rendering requires models to be incredibly efficient, balancing visual quality with the need for high frame rates on a wide range of hardware. A beautiful 3D car model designed for rendering might have millions of polygons and dozens of high-resolution textures, which would bring a game engine to its knees. Adapting such an asset for interactive experiences involves strategic optimization techniques, ensuring the car looks great while maintaining smooth performance.

The polygon budget for a game-ready car asset can vary significantly. For a high-fidelity car in a modern racing game, the main playable vehicle (LOD0) might be around 100,000 to 200,000 triangles, while background vehicles could be as low as 10,000-20,000. Mobile AR/VR applications demand even stricter limits, sometimes requiring a car model to be under 50,000 triangles total. This intense focus on efficiency drives many of the optimization techniques detailed below, ensuring that the car not only looks good but also runs smoothly within the demanding constraints of a game engine.

LODs and Polygon Budgeting for Performance

Level of Detail (LOD) is a crucial optimization technique for game assets. Instead of rendering a single, high-polygon model at all distances, LODs involve creating multiple versions of the same model with progressively lower polygon counts. The game engine then swaps between these versions based on the object’s distance from the camera.

- LOD0 (Hero Asset): Highest detail, used when the car is close to the camera (e.g., 100,000 – 200,000 triangles).

- LOD1 (Medium Detail): Reduced detail, used at mid-distances (e.g., 30,000 – 50,000 triangles).

- LOD2 (Low Detail): Significantly reduced, used at further distances (e.g., 5,000 – 10,000 triangles).

- LOD3 (Very Low Detail/Imposter): Very basic shape or even a 2D billboard for extreme distances (e.g., <1,000 triangles).

Creating LODs can be done manually through retopology or automatically using poly-reduction tools within software like Maya, 3ds Max, Blender, or game engines like Unity and Unreal Engine. The challenge is to maintain visual consistency across LODs, ensuring that the silhouette and key details remain recognizable even at lower polygon counts. Normal maps are often baked from the high-poly model onto the lower-poly LODs to retain surface detail without adding geometry.

Texture Atlasing, Draw Calls, and Asset Management

Beyond polygon count, texture usage and draw calls are significant performance bottlenecks in game engines. A “draw call” is a command sent from the CPU to the GPU to render a batch of objects. Each time a new material or texture is needed, it often incurs a new draw call. For a car model composed of many separate parts (body, wheels, windows, interior) each with its own material, this can quickly add up.

Texture Atlasing: This technique involves combining multiple smaller texture maps (e.g., for interior buttons, emblems, small trim pieces) into a single, larger texture atlas. This allows the game engine to render many different surfaces using a single material, thereby drastically reducing draw calls and improving performance.

Mesh Instancing: For identical parts like wheels, using mesh instancing (where the same mesh data is reused multiple times) can further optimize performance.

Rigging and Animation: If the car needs to interact with the environment (e.g., suspension deformation, opening doors, turning wheels), it will require proper rigging with an armature and relevant animations. This needs to be carefully set up to be game-engine friendly, using skeletal meshes and inverse kinematics where appropriate.

Engine-Specific Shaders: Both Unity and Unreal Engine provide powerful PBR material systems. Artists need to understand how to translate their PBR textures into the engine’s material graphs, optimizing for features like reflections, clear coat, and real-time lighting. When sourcing game-ready 3D car models, platforms such as 88cars3d.com often provide models with pre-optimized meshes and PBR texture sets, configured for direct import into popular game engines.

Expanding Horizons: AR/VR, 3D Printing, and File Formats

The utility of high-quality 3D car models extends far beyond traditional rendering and game development. They are increasingly vital for cutting-edge applications in Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR), enabling immersive experiences for automotive configurators, training simulations, and virtual showrooms. Furthermore, these digital assets can be transformed into physical objects through 3D printing, opening up possibilities for prototyping, scale models, and custom car parts. Navigating these diverse applications requires an understanding of specific optimization strategies and the myriad of file formats that facilitate interoperability across different software and platforms.

The demands for AR/VR are often the most stringent, pushing artists to achieve visual fidelity with minimal resources. A typical AR/VR car model might aim for a poly count under 75,000-100,000 triangles, with textures aggressively optimized to 1K or 2K resolution, often using texture atlases. 3D printing, conversely, requires a watertight mesh with specific considerations for physical structure, regardless of polygon count. Each application presents its unique set of challenges and technical requirements that artists must master.

Optimizing for AR/VR Experiences

AR/VR environments impose extremely strict performance budgets. Achieving smooth frame rates (often 60-90 frames per second per eye) is critical to prevent motion sickness and ensure a comfortable, immersive experience. This means aggressive optimization of 3D car models:

- Ultra-Low Polygon Counts: Models must be heavily optimized, often using aggressive LODs. Complex interiors might be simplified or even removed for casual AR experiences.

- Optimized Textures: Texture resolutions are typically lower (1K-2K), and extensive use of texture atlasing is common to reduce draw calls.

- Baked Lighting: For static elements, baking ambient occlusion and indirect lighting into vertex colors or lightmaps can save significant real-time computation.

- Single-Pass Stereo Rendering: VR renders the scene twice (once for each eye). Single-pass stereo rendering optimizes this by rendering both eyes simultaneously, which is a key performance booster.

- Scale and Orientation: Ensuring the model is at the correct real-world scale and has a consistent up-axis (e.g., Y-up or Z-up) is crucial for accurate AR placement and VR interaction.

Specific file formats like GLB (glTF Binary) and USDZ (Universal Scene Description Zip) are preferred for AR/VR due to their compact size, PBR material support, and ability to embed animations and hierarchies, making them ideal for web-based and mobile AR applications.

Preparing 3D Models for Physical Production (3D Printing)

Transforming a digital 3D car model into a physical object via 3D printing requires a different set of considerations. The primary concern is mesh integrity:

- Watertight Mesh: The model must be “watertight” or “manifold,” meaning it has no holes, non-manifold edges, or inverted normals. Every surface must enclose a solid volume. 3D printing software needs to understand what is “inside” and “outside” the object.

- Mesh Repair: Tools like Netfabb, Meshmixer, or Blender’s 3D Print Toolbox can identify and repair common mesh errors that would cause printing failures.

- Wall Thickness: The mesh must have sufficient wall thickness to be physically viable. Extremely thin features might break during printing or handling. This often requires artists to add thickness to single-plane surfaces.

- Scale and Resolution: The model must be scaled correctly for the desired print size. The polygon density needs to be high enough to capture fine details, but not excessively high, as it can slow down slicing software.

Common file formats for 3D printing include STL (Stereolithography), which is a triangulated mesh format, and OBJ. These formats store only geometry, so colors and materials are typically handled by the slicing software or defined separately.

Navigating File Formats and Interoperability

The world of 3D software relies on a multitude of file formats, each with its strengths and intended purpose. Understanding these formats is crucial for seamless asset exchange and deployment:

- FBX (Filmbox): Developed by Autodesk, FBX is arguably the most widely used interchange format in 3D. It supports geometry, materials, textures, animations, rigging, cameras, and lights, making it ideal for moving complex assets between software like 3ds Max, Maya, Blender, Unity, and Unreal Engine.

- OBJ (Wavefront Object): A simple, universal format for geometry. It’s highly compatible but doesn’t natively support animations or advanced material properties, often relying on accompanying .MTL (material) files for basic color and texture information. Great for static meshes.

- GLB/glTF (Graphics Language Transmission Format): An open standard from Khronos Group, designed for efficient transmission and loading of 3D scenes and models by engines and applications. It’s become the “JPEG of 3D” for web, AR/VR, and real-time applications, supporting PBR materials, animations, and scene hierarchy in a compact binary format (GLB).

- USD/USDZ (Universal Scene Description): Developed by Pixar, USD is a powerful framework for interchange and collaborative scene description, particularly for large, complex production pipelines. USDZ is Apple’s package format for USD, optimized for AR applications on iOS. It excels at handling complex scene graphs and layering.

- STL (Stereolithography): A basic triangulated mesh format primarily used for 3D printing and CAD. It contains only geometry data.

When sourcing models, especially high-quality 3D car models, platforms like 88cars3d.com typically offer assets in multiple popular formats (e.g., FBX, OBJ) to ensure broad compatibility, allowing artists to integrate them into their preferred workflow with minimal conversion headaches.

Conclusion

The journey from a blank canvas to a stunning, fully realized 3D car model is a intricate dance between artistic vision and technical prowess. We’ve explored the critical importance of clean topology and precise edge flow as the bedrock of any high-quality automotive asset. We’ve delved into the science of PBR materials and meticulous UV mapping, revealing how they transform inert polygons into lifelike surfaces that interact realistically with light. From the art of crafting cinematic renders with advanced lighting and renderer-specific strategies to the pragmatic demands of game engine optimization, LODs, and texture atlasing, the technical landscape is vast and challenging.

Furthermore, the expanding frontiers of AR/VR and 3D printing continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible, requiring specialized optimization techniques and an understanding of diverse file formats like GLB, USDZ, and STL. Mastering these technical aspects is not just about proficiency; it’s about unlocking the full potential of your 3D car models, ensuring they look exceptional and perform flawlessly across every application. As the digital realm continues to evolve, the demand for artists and developers who can deliver high-quality, technically sound 3D car assets will only grow. By continuously refining your skills and embracing industry best practices, you can drive your creativity to new heights and accelerate your impact in the exciting world of 3D visualization.

Featured 3D Car Models

Nissan Micra 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Nissan Micra 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Eclipse GT 2001 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Eclipse GT 2001 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

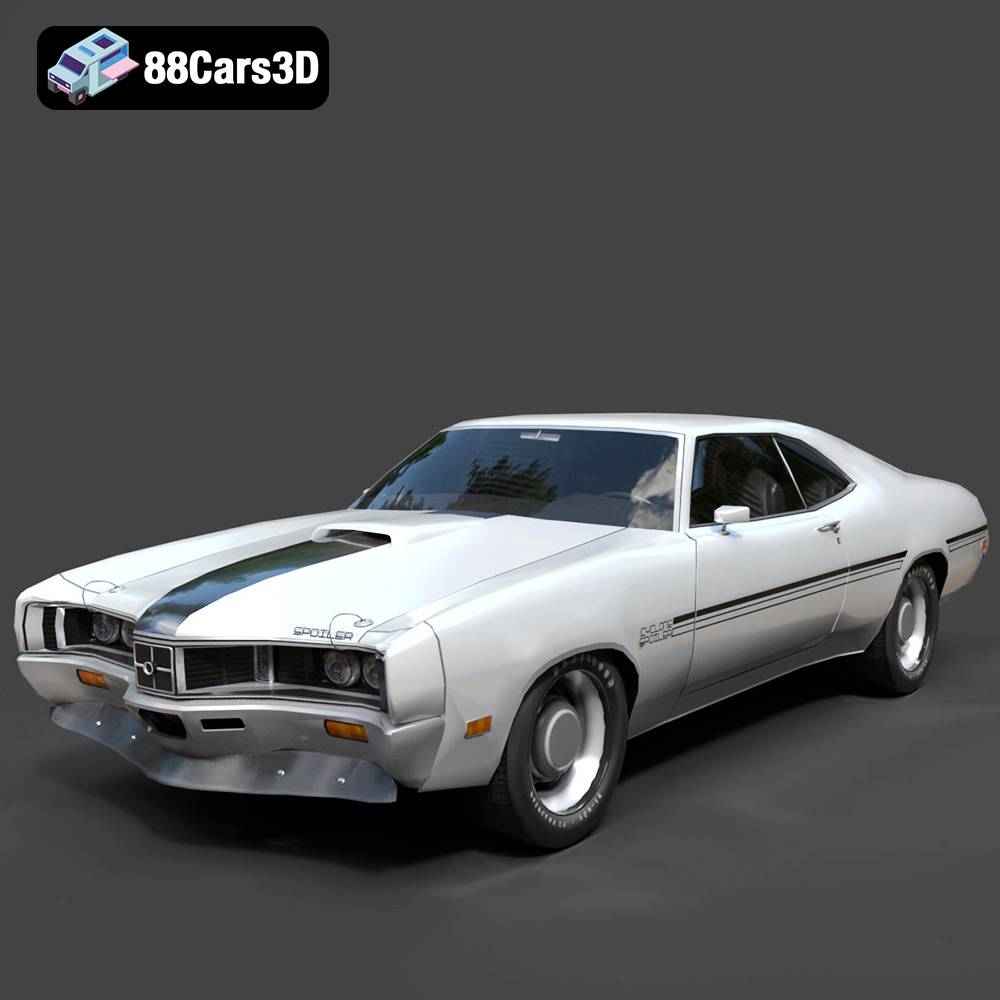

Mercury Cyclone Spoiler 1970 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercury Cyclone Spoiler 1970 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Opel Astra 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Opel Astra 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VIII 2003 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VIII 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Peugeot 307 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Peugeot 307 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Peugeot 207 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Peugeot 207 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VI 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VI 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99

Nissan Moco 007 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Nissan Moco 007 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $4.99