The Foundational Challenge: Why Car Paint Demands PBR

The gleam of a perfectly rendered car paint job is often the ultimate benchmark for a 3D artist’s skill. More than just a simple color, a truly photorealistic car finish encapsulates a symphony of subtle optical phenomena: the deep reflections of the clear coat, the shimmering dance of metallic flakes, and the nuanced interaction with every light source. It’s a challenging feat, making car paint one of the most complex materials to faithfully replicate in the digital realm.

For automotive designers, game developers, and visualization artists, achieving this level of realism is paramount. It’s not just about aesthetics; it’s about conveying quality, authenticity, and the very essence of a vehicle’s design. This article will peel back the layers, delving deep into the anatomy of next-gen car paint shaders, exploring the intricate details that transform a flat texture into a breathtakingly lifelike surface. We’ll focus heavily on the Physically Based Rendering (PBR) workflow, which has become the industry standard for its ability to produce consistent and believable results across diverse lighting conditions.

The Foundational Challenge: Why Car Paint Demands PBR

Traditional rendering techniques often struggled with the multifaceted nature of car paint. Simple Phong or Blinn shaders, while useful for many materials, couldn’t accurately capture the energy conservation, layered reflectivity, and complex light scattering inherent in automotive finishes. This led to surfaces that looked “fake” or overly uniform, lacking the dynamic interplay of light and shadow seen in the real world.

Enter Physically Based Rendering (PBR). The PBR workflow is a paradigm shift, focusing on simulating how light interacts with materials in a physically plausible way. This means adhering to real-world physics, such as energy conservation (light cannot be created or destroyed, only absorbed or reflected) and accurate microfacet distribution models. For materials like PBR automotive paint, this approach is not just beneficial; it’s essential. It allows artists to define material properties that behave correctly under any lighting scenario, leading to predictable and, most importantly, photorealistic outcomes.

The complexity of car paint arises from its layered structure, each layer contributing uniquely to the final visual effect. From the base color to the metallic flakes and the protective clear coat, understanding these individual components and how they combine is the first step toward crafting truly next-gen shaders.

Deconstructing the Layers: The Multi-Layered Material System

A typical car paint is not a monolithic material but a sophisticated stack of distinct layers, each with its own optical properties. To accurately simulate it, we must model these layers individually and understand their interaction. This multi-layered approach is fundamental to creating a compelling high-fidelity car rendering.

The Base Coat: Foundation of Color and Opacity

The base coat is the primary pigment layer, responsible for the car’s core color. In PBR terms, this is typically represented by the ‘albedo’ or ‘base color’ map. For non-metallic paints, the base coat will exhibit diffuse reflection, scattering light broadly. Its roughness value will determine how much diffuse blur it has before the clear coat is applied. Sometimes, a subtle amount of subsurface scattering can be simulated within the base coat for extremely deep, rich solid colors, though this is often an advanced optimization.

For metallic and pearlescent paints, the base coat isn’t just about diffuse color; it’s also where the special effect pigments reside. This brings us to the next critical component.

The Metallic Flake Shader: The Shimmering Heartbeat

This is arguably the most challenging and visually impactful layer to simulate. Metallic or pearlescent flakes are tiny, reflective particles suspended within a semi-transparent colored binder, just beneath the clear coat. Their primary function is to catch and reflect light, creating a distinct sparkle and a phenomenon known as ‘flop’ or ‘light/dark travel’. This means the color and brightness appear to shift depending on the viewing angle.

To implement a realistic Metallic flake shader, you’ll need to consider:

- Flake Distribution: Typically represented by a noise texture or a procedural pattern, controlling the density and randomness of the flakes.

- Flake Size and Shape: Smaller flakes produce a finer, more uniform sparkle; larger flakes are more pronounced. While often simplified as points, some advanced techniques use actual micro-geometry or normal maps to simulate their individual surfaces.

- Flake Orientation: This is crucial. Real-world flakes tend to align roughly parallel to the surface, but slight variations in orientation are what create the sparkling effect. A ‘flake normal map’ can be used to drive individual flake orientations, creating a more organic, less uniform sparkle.

- Flake Reflectivity and Color: These are typically metallic, meaning they reflect light rather than absorb it. Their color can influence the overall perceived hue of the paint, especially in pearlescent finishes.

In many modern renderers, the metallic flake shader is achieved by layering a very fine, highly reflective noise pattern (driven by flake intensity, size, and normal maps) over the base color, then blending it under the clear coat. The ‘flop’ effect is often a complex interplay of reflection angles, making shader graph development essential for precise control.

The Clear Coat Material: The Glossy Dominator

The clear coat is the outermost, transparent, and highly reflective layer that gives car paint its characteristic gloss and depth. It’s a crucial component for PBR automotive paint realism, acting as a protective shell while also defining the primary reflections seen on the car’s surface. Simulating a convincing Clear coat material requires careful attention to several PBR parameters:

- Index of Refraction (IOR): For typical clear coats (lacquer, urethane), an IOR of around 1.4-1.5 is appropriate. This determines how much light is reflected versus refracted (passed through) at the surface.

- Roughness/Glossiness: This value dictates the sharpness of reflections. A brand-new, polished car will have very low roughness (high gloss), resulting in sharp, mirror-like reflections. Imperfections, dust, or wear can be introduced with a roughness map.

- Thickness: While often simplified, the clear coat has a physical thickness. This can be important for subtle absorption effects (tinting) or even very minor refraction of underlying layers, especially if subsurface scattering is considered.

- Absorption/Attenuation: Perfect clear coats are completely transparent. However, some car paints might incorporate very subtle tints into the clear coat, or it might subtly absorb light over distance, which can be simulated with an attenuation color or volume absorption settings.

The clear coat’s reflections are typically Fresnel-driven, meaning reflections are stronger at glancing angles and weaker when viewed head-on. This effect is automatically handled by most PBR shading models but is critical to its visual authenticity.

The Core of PBR Automotive Paint: Understanding BRDFs and Energy Conservation

At the heart of any Physically Based Rendering (PBR) workflow lies the Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF). This mathematical function describes how light is reflected from an opaque surface. For car paint, understanding the right BRDF models and energy conservation principles is paramount to achieving visual fidelity.

BRDF Models for Car Paint

Most modern PBR renderers utilize microfacet BRDFs, which assume a surface is composed of tiny, randomly oriented micro-facets. The aggregate reflection from these micro-facets determines the macroscopic reflection behavior. Common models include:

- GGX (Trowbridge-Reitz): This is the most prevalent BRDF model due to its excellent balance of realism and performance. It produces sharper, more defined specular lobes and a more realistic falloff at glancing angles, closely matching real-world materials like the highly polished clear coat on a car.

- Ward: While less common for general PBR, the Ward model can be useful for simulating anisotropic highlights, which are crucial for certain car paint effects, especially brushed metals or specific paint finishes. However, GGX often provides a more robust foundation.

For a multi-layered material like car paint, you’re essentially stacking these BRDFs. The clear coat uses its own BRDF (typically GGX with low roughness) for its reflections, while the underlying base coat and metallic flakes contribute their own reflective properties that are then seen through the clear coat’s refractions.

The Principle of Energy Conservation

Energy conservation dictates that a surface cannot reflect more light than it receives. In PBR, this means that as a surface becomes more reflective (less rough, more metallic), it must become less diffuse. The sum of reflected and absorbed light must equal the incoming light. This prevents materials from looking unnaturally bright or “glowing” under intense illumination.

For car paint, energy conservation is implicitly handled when you correctly set up your base color, metallic, and roughness maps. The metallic property controls the balance between diffuse and specular reflections at the base coat level. The clear coat then adds another layer of specular reflection on top, but its interaction with the underlying layers still adheres to this fundamental principle, ensuring a believable distribution of light.

Mastering Anisotropic Highlights for Dynamic Reflections

While isotropic reflections (where reflections are uniform in all directions) work for many materials, car paint often requires a more nuanced approach, particularly for metallic or specialized finishes. This is where Anisotropic highlights come into play, offering a critical step toward high-fidelity car rendering.

What is Anisotropy?

Anisotropy refers to the directional dependence of a material’s properties. For reflections, it means that highlights appear stretched or elongated in a specific direction, rather than perfectly round. Think of the concentric rings of light you see on a brushed metal surface or the way light streaks across certain types of paint. This stretching is caused by micro-grooves or aligned micro-facets on the surface that scatter light preferentially in one direction.

Why is it Crucial for Car Paint?

While the primary clear coat reflection on a car is largely isotropic, certain aspects of car paint greatly benefit from anisotropic simulation:

- Metallic Flakes: Individual metallic flakes, while small, can collectively contribute to a subtle anisotropic sheen, especially if they have a preferred alignment.

- Specialized Finishes: Some custom car paints, particularly those with highly directional pigments or unique textures, exhibit strong anisotropic properties.

- Wear and Tear: Scratches or polishing marks on the clear coat itself will often appear as anisotropic streaks, significantly enhancing realism.

Achieving Anisotropic Highlights in Your Shader

Implementing anisotropic highlights typically involves an additional input in your shader: a ‘tangent’ or ‘anisotropy direction’ map. This map defines the local direction of the stretched highlight. Here’s how it’s commonly done:

- Tangent Map Creation:

- Procedural: For simple, uniform anisotropy (e.g., brushed metal effect), you can often generate a tangent vector procedurally based on the object’s UVs or local space.

- Texture-Based: For more complex or localized anisotropy (e.g., specific scratch patterns), you’ll need a tangent map (often stored in an RGB texture, where R and G channels represent the U and V tangent directions). This map guides the stretching of the reflections.

- Shader Node Setup: In your shader graph development, you’ll feed this tangent map into the anisotropy input of your material. Most advanced PBR shaders (like those found in Unreal Engine, Unity’s HDRP, Blender Cycles, V-Ray, or Corona) will have a dedicated anisotropy parameter or node that works in conjunction with your roughness map. The roughness determines the blurriness of the reflection, while the anisotropy factor and direction map determine how that blur is stretched.

- Controlling Intensity and Direction: You’ll also typically have an ‘anisotropy strength’ parameter to control how pronounced the stretching is. Experimentation is key to finding the right balance for your specific paint finish.

The visual impact of correctly implemented anisotropic highlights can be profound, adding a layer of subtle realism that elevates your renders from good to exceptional. This is especially true when creating assets for 88cars3d.com, where attention to such fine details is paramount for high-quality models.

Optimizing Your Physically Based Rendering (PBR) Workflow for Car Paint

Creating beautiful shaders is one thing; integrating them into an efficient and effective production pipeline is another. An optimized Physically Based Rendering (PBR) workflow for car paint ensures consistency, performance, and scalability across your projects, from real-time game assets to pristine offline renders.

Texture Creation: The Lifeblood of Your Shader

High-quality textures are non-negotiable for PBR automotive paint. Consider the following:

- Base Color (Albedo): This is your primary color. For solid paints, it’s straightforward. For metallics, it defines the color of the paint binder. Ensure it’s desaturated for metallic surfaces as the metallic map takes over reflectivity.

- Roughness Map: This map is critical for defining the glossiness of your clear coat. Use subtle noise patterns and grime maps to break up perfectly uniform reflections, creating realistic imperfections like dust, fingerprints, or micro-scratches. These small details dramatically enhance the high-fidelity car rendering.

- Metallic Map: For the metallic flakes, this map (often a grayscale value) dictates where metallic behavior occurs. For a true PBR approach, the metallic property of the flakes themselves is usually 1 (fully metallic), and the map controls their visibility.

- Normal Map: Essential for adding fine surface details without adding geometry. This can simulate orange peel effect, subtle ripples in the paint, or the directionality for anisotropic reflections.

- Anisotropy Direction Map: As discussed, this map (often a 2-channel or packed RGB texture) defines the stretching direction for anisotropic reflections.

- Flake Map (Optional): For very custom flake patterns, a texture map might define flake density or unique color variations for procedural flake systems.

When creating these, always work in a linear color space and ensure your textures are properly calibrated for PBR, avoiding “legacy” texture authoring mindsets.

UV Mapping: Precision for Perfect Reflections and Flakes

Proper UV mapping is often overlooked but is crucial for car paint. Here’s why:

- Consistent Flake Distribution: If your metallic flake shader uses a texture map for distribution, well-organized UVs ensure the flakes appear consistent in size and density across the entire vehicle. Avoid stretching or overlapping UVs.

- Seamless Imperfections: Roughness maps, normal maps for orange peel, and dirt textures all rely on clean UVs to wrap seamlessly around the complex curves of a car model.

- Anisotropy Direction: If you’re using UV-driven procedural anisotropy, the UV layout directly dictates the direction of the stretched highlights. Ensure they flow correctly along the body panels.

For best results, aim for a single, non-overlapping UV set for the main car body that is dedicated to the paint shader, making the shader graph development cleaner and more predictable.

Balancing Performance with Visual Fidelity

The level of detail in your car paint shader often depends on your target platform:

- Real-time (Games/Interactive): Optimize aggressively. Use simpler clear coat approximations (single-layer PBR with a clear coat ‘hack’ or dedicated layered shader), texture packing (e.g., roughness, metallic, AO in one RGB map), and carefully manage metallic flake shader complexity. Procedural flakes can be expensive; consider pre-baked flake normal maps.

- Offline Rendering (Arch-Viz/Film): You have more freedom. Utilize complex multi-layered shaders, subtle subsurface scattering for the clear coat, volumetric absorption, and highly detailed texture maps. The focus here is on absolute realism, not frame rate.

Always profile your shaders. A complex shader graph can quickly bog down render times, even on powerful hardware.

Lighting Setup: Revealing the Paint’s True Beauty

Even the best car paint shader will look flat under poor lighting. A well-designed lighting setup is essential for showcasing high-fidelity car rendering:

- HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image): Use HDRIs of real-world environments (studio, outdoor, industrial) to provide realistic ambient illumination and reflections. They are incredibly effective at making car paint pop.

- Area Lights/Studio Lights: Supplement HDRIs with carefully placed area lights to emphasize reflections, define contours, and simulate studio lighting setups. Use soft, large lights for a luxurious feel, or sharper lights for a more dramatic effect.

- Backlighting: A strong backlight can beautifully reveal the edges and curves of the car, enhancing the sense of depth and highlighting the clear coat’s sheen.

Experiment with different lighting scenarios to see how your PBR automotive paint reacts. This iterative process is crucial for fine-tuning the shader’s parameters.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Overly Reflective/Rough Clear Coat: A common mistake is making the clear coat too perfect (zero roughness) or too rough. Real car paint has subtle imperfections.

- Incorrect IOR: Using a default IOR (like 1.52 for glass) for clear coat is often inaccurate. Use values closer to 1.4-1.5 for lacquer/urethane.

- Uniform Flake Distribution: Perfectly uniform procedural flakes can look artificial. Introduce subtle noise for randomness.

- Lack of Micro-Imperfections: Pristine surfaces often look fake. Add subtle scratches, dust, or fingerprints via roughness and normal maps.

- Color Space Issues: Not working in a linear color space or mismanaging texture gamma can lead to washed-out or overly dark results.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Photorealistic Automotive Finishes

Crafting next-gen car paint shaders is a sophisticated blend of technical understanding and artistic finesse. It requires a deep dive into the physics of light, a meticulous deconstruction of material layers, and a precise execution of texture and shader parameters within a robust Physically Based Rendering (PBR) workflow.

From the foundational base coat to the shimmering Metallic flake shader, the defining Clear coat material, and the subtle yet powerful Anisotropic highlights, each component plays a vital role in creating a truly believable and captivating automotive finish. Mastering these elements through thoughtful shader graph development and an optimized pipeline is what separates good renders from truly exceptional ones.

Whether you’re developing assets for cutting-edge games or producing stunning visualizations, the effort invested in perfecting your car paint shaders will pay dividends in realism and visual impact. Embrace the complexity, pay attention to the details, and your 3D vehicles will truly shine.

Looking for a head start with meticulously crafted 3D automotive models? Explore the extensive library at 88cars3d.com, where you’ll find high-quality assets designed with PBR workflows in mind, ready to be enhanced with your next-gen car paint shaders. Elevate your projects today!

Featured 3D Car Models

Suzuki SX4-002 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Suzuki SX4-002 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Tesla Model S 2024 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Tesla Model S 2024 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Subaru Impreza WRX STi-002 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Subaru Impreza WRX STi-002 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Mark II (X100) 1998 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Mark II (X100) 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Corona 1985 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Corona 1985 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Mark II X81 1990 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Mark II X81 1990 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota iQ EV 2012 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota iQ EV 2012 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Aygo 2013 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Aygo 2013 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Crown S180 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Crown S180 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Celica 2004 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Celica 2004 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Corolla AE100 1992 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Corolla AE100 1992 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Mark II X110 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Mark II X110 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Corolla 2020 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Corolla 2020 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $10

Toyota Yaris 2020 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Yaris 2020 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Volkswagen Beetle 2012 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Beetle 2012 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Matrix 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Matrix 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Yaris Sedan 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Yaris Sedan 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Volkswagen Golf R-004 2024 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf R-004 2024 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Volkswagen Golf 5 Door 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf 5 Door 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Premio 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Premio 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Opa 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Opa 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Volkswagen Polo 5 Door 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Polo 5 Door 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Prius 2024 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Prius 2024 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Yaris 1999 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Yaris 1999 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Toyota Supra 2020 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Toyota Supra 2020 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $9.9

Volkswagen New Beetle 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen New Beetle 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $14.99

Volkswagen Jetta 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Jetta 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $18.99

Volkswagen Golf 3-Door 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf 3-Door 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $14.99

Volvo V70 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo V70 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $14.99

Volkswagen Bora 2004 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Bora 2004 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $14.99

Volkswagen Lupo 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Lupo 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $19.99

Volkswagen Passat B5 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Passat B5 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $19.99

Volkswagen Passat CC 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Passat CC 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $19.99

Volkswagen Golf V 2006 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf V 2006 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $19.99

Volvo S60 R-Design 2024 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo S60 R-Design 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $19.99

Volkswagen Passat 2025 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Passat 2025 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volkswagen Passat Variant B6 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Passat Variant B6 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volkswagen Phaeton W12 2004 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Phaeton W12 2004 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volkswagen Scirocco 2015 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Scirocco 2015 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volvo S60 2024 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo S60 2024 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volkswagen Polo 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Polo 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volkswagen Golf 5-Doors 2018 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf 5-Doors 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $25.99

Volvo C70 T5 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo C70 T5 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volvo S40 Sedan 2004 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo S40 Sedan 2004 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volvo C30 BEV 2012 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo C30 BEV 2012 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volvo C70 1998 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo C70 1998 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mazda B-Series 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mazda B-Series 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercsedes Benz Z3-006 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercsedes Benz Z3-006 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mazda RX-7 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mazda RX-7 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volvo VCC-003 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo VCC-003 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

GAZ 3110 Pickup 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the GAZ 3110 Pickup 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mazda 626 GF 1997 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mazda 626 GF 1997 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volvo S80 2011 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volvo S80 2011 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volkswagen Touran restyle-006 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Touran restyle-006 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Skoda Octavia Scout 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Skoda Octavia Scout 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Volkswagen Golf V 2006 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Volkswagen Golf V 2006 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mazda CX-7 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mazda CX-7 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mazda Familia 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mazda Familia 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

GAS 21 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the GAS 21 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz SL500 AMG (R129) 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SL500 AMG (R129) 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz S-Class W221 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz S-Class W221 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz E-Class W212 2009 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz E-Class W212 2009 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz E-class Estate S212 2009 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz E-class Estate S212 2009 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz 190 W201 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz 190 W201 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz C230 SportCoupé 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C230 SportCoupé 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz SLK 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLK 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes 600 SEC W140 1992 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes 600 SEC W140 1992 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes S-Class 2010 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes S-Class 2010 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

McLaren MP4-12C-001 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the McLaren MP4-12C-001 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz SLK 350 2005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLK 350 2005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz SL 65 AMG 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SL 65 AMG 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz S500 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz S500 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz S55 W220 AMG 1999 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz S55 W220 AMG 1999 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz CLA45 AMG 2017 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CLA45 AMG 2017 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CL65 C215 AMG 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CL65 C215 AMG 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz A45 2021 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz A45 2021 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz 300SL 1955 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz 300SL 1955 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz 190SL 1955 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz 190SL 1955 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

Mercedes-Benz W124 Brabus V12 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz W124 Brabus V12 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $23.99

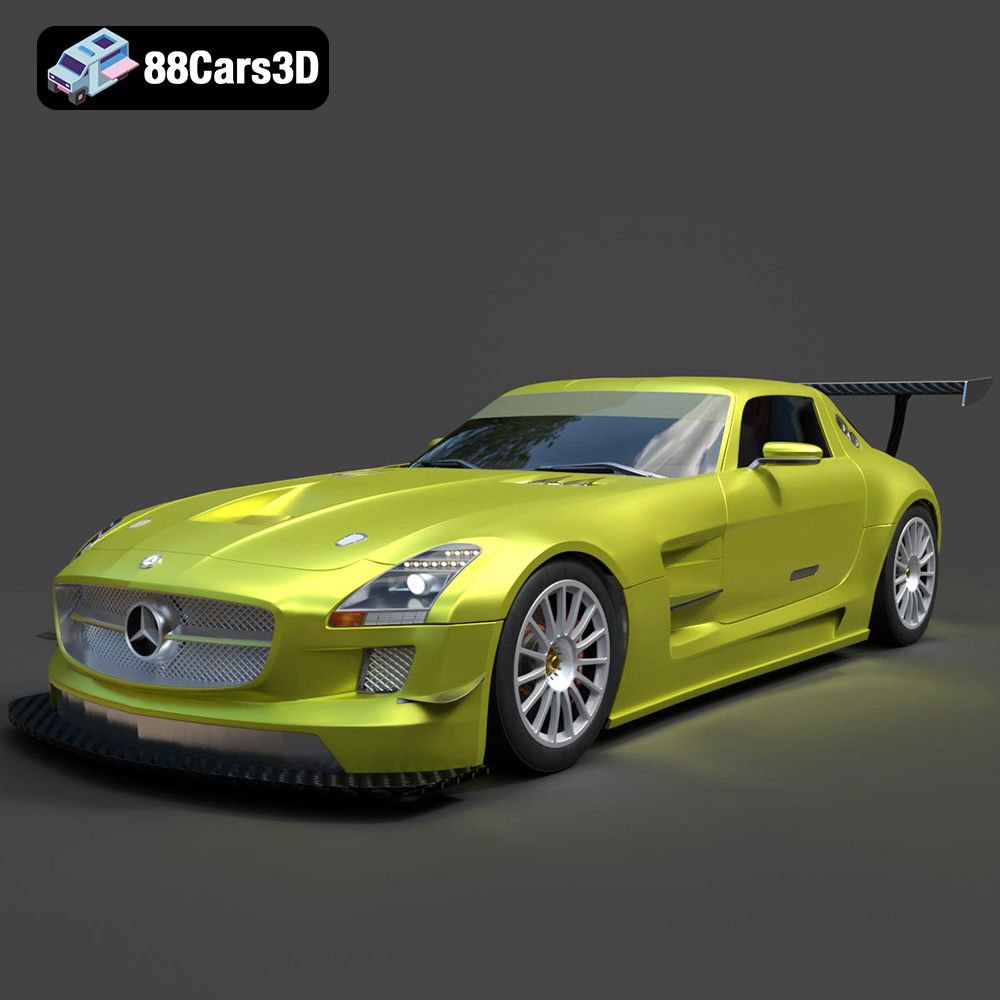

Mercedes-Benz SLS AMG GT3-002 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz SLS AMG GT3-002 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz C-Class-001 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C-Class-001 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz B-Klasse 2023 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz B-Klasse 2023 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz A-Klasse W168 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz A-Klasse W168 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz 500SL 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz 500SL 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz 500SEC 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz 500SEC 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz Citan 2025 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz Citan 2025 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz C63 AMG 2012 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C63 AMG 2012 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz E-Class S211 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz E-Class S211 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CLS63 AMG (C218) 2014 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CLS63 AMG (C218) 2014 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CLS-Klasse 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CLS-Klasse 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CLS 500 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CLS 500 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CL-Klasse 2001 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CL-Klasse 2001 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz C-Klasse Sportcoupe 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C-Klasse Sportcoupe 2000 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz C-Klasse 204 2011 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C-Klasse 204 2011 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz C-Class Sedan 2000 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz C-Class Sedan 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes E-Class w124 Kombi 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes E-Class w124 Kombi 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz CL6540-005 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz CL6540-005 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes E-Class w124 Coupe 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes E-Class w124 Coupe 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99

Mercedes-Benz E-Klasse 63 AMG 3D Model

Texture: Yes

Material: Yes

Download the Mercedes-Benz E-Klasse 63 AMG 3D Model featuring clean geometry, realistic detailing, and a fully modeled interior. Includes .blend, .fbx, .obj, .glb, .stl, .ply, .unreal, and .max formats for rendering, simulation, and game development.

Price: $38.99