One Model, Two Worlds: Optimizing 3D Car Models for Photorealistic Renders vs. Real-Time Performance

One Model, Two Worlds: Optimizing 3D Car Models for Photorealistic Renders vs. Real-Time Performance

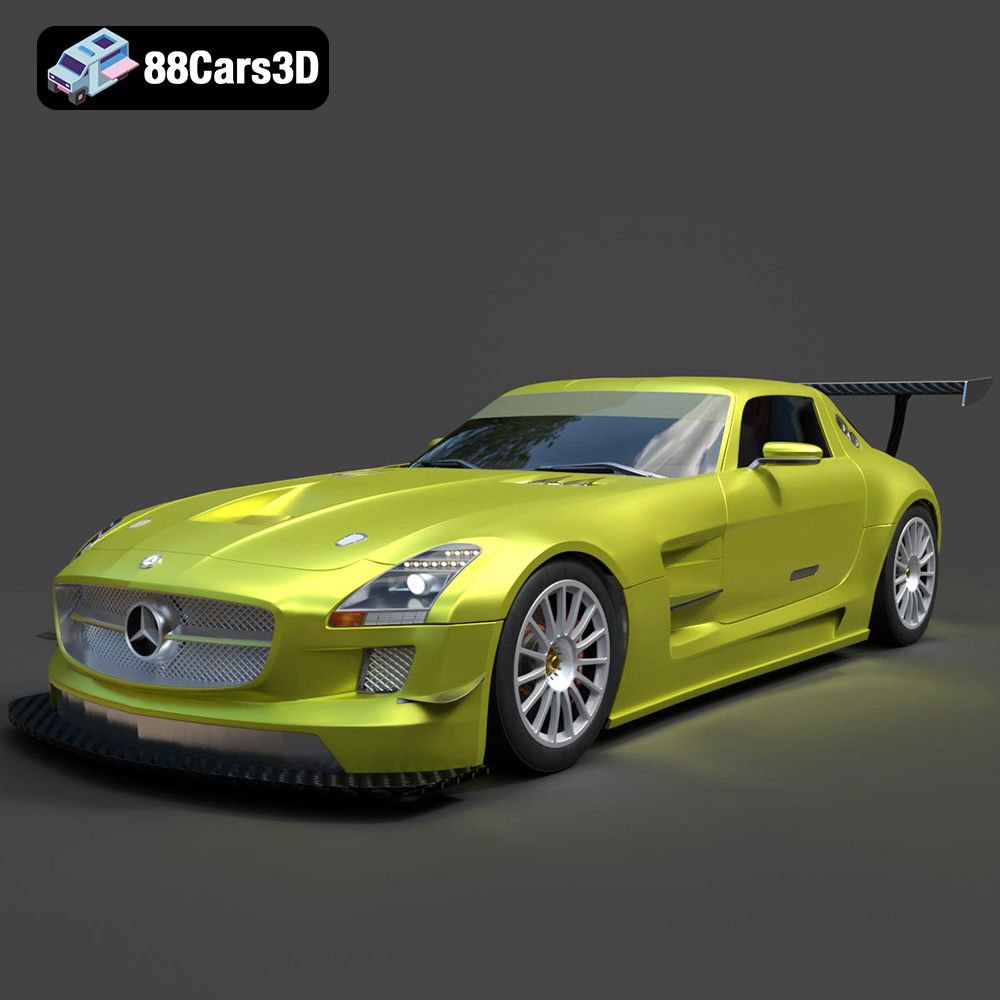

There’s a universal thrill in seeing a perfectly crafted 3D car model. The flawless paint, the intricate interior, the glint of light off a chrome trim—it’s the culmination of immense artistic and technical skill. But once you acquire that pristine digital vehicle, its journey has only just begun. The path it takes next diverges dramatically depending on its final destination: a breathtaking frame in a cinematic automotive rendering or a high-performance, interactive asset in a video game.

A common misconception is that a single “high-quality” model is a one-size-fits-all solution. In reality, a model optimized for a V-Ray or Corona render would cripple a game engine, while a model built for Unreal Engine would lack the nuance and detail required for a 4K marketing shot. Understanding how to adapt a master model for these distinct pipelines is the key to unlocking its full potential. This guide will walk you through the technical workflows, critical considerations, and optimization strategies for preparing 3D car models for both high-fidelity rendering and real-time game development.

The Foundation: Anatomy of a High-Quality Source Model

Before any optimization can begin, you must start with a solid foundation. Whether you’re creating a model from scratch or purchasing one from a specialized marketplace, the quality of the source asset will dictate the success of your entire project. A poorly constructed model will lead to hours of frustrating cleanup work, while a professional-grade asset provides a clean slate for any pipeline.

Topology and Edge Flow

The bedrock of a great 3D model is its topology—the arrangement of its polygons. A high-quality source model should be built almost exclusively with quadrilaterals (quads). This clean, grid-like structure is predictable and subdivides perfectly, which is essential for creating smooth, high-resolution surfaces for rendering. Look for clean edge loops that follow the natural contours and curvature of the car’s body panels. This ensures that when a subdivision modifier (like 3ds Max’s TurboSmooth or Blender’s Subdivision Surface) is applied, the surfaces remain taut and free of pinching or artifacts.

Clean Hierarchy and Logical Naming

A professional 3D car model is not a single, monolithic mesh. It’s a complex assembly of hundreds of individual parts. A well-organized source file will have a logical hierarchy. For example, the “Wheel_LF” (Left Front) object should be a parent to the “BrakeCaliper_LF,” “BrakeDisc_LF,” and “Tire_LF.” All these components should have their pivot points set correctly for realistic animation, such as wheels rotating on their central axis and doors swinging on their hinges. This meticulous organization saves countless hours when it comes to rigging, animation, or separating materials.

UV Unwrapping Strategy

UVs are the 2D coordinates that tell the 3D software how to apply a 2D texture to a 3D surface. For a high-end source model, you’ll often encounter a UDIM (U-Dimension) workflow. This technique spreads the UVs across multiple texture tiles, allowing for incredibly high-resolution textures on different parts of the car. While fantastic for rendering, this is a key area that requires significant changes for a real-time game asset pipeline, as we’ll explore later.

The High-Fidelity Path: Prepping for Photorealistic Automotive Rendering

When your goal is a stunning, photorealistic still image or animation for advertising, film, or a portfolio, performance is secondary to visual fidelity. Here, the aim is to add detail and complexity, pushing the source model to its absolute limits.

Non-Destructive Subdivision Workflows

This is where clean, quad-based topology pays off. In software like 3ds Max or Blender, you’ll use a subdivision modifier. The key is to work non-destructively. Instead of collapsing the modifier stack and baking the high polygon count into the model, you keep it live. This allows you to add finer details—like panel gaps, edge bevels, or welding seams—on the base mesh while seeing the final, smoothed result in the viewport. For hero shots, it’s common to use 2 to 3 levels of subdivision, pushing the polygon count into the tens of millions for unparalleled smoothness on curved surfaces.

Complex Materials and Layered Shaders

Photorealistic rendering is a game of nuance. A simple “red” material won’t cut it for car paint. In render engines like V-Ray or Corona, you’ll build complex, multi-layered shaders. A typical car paint material might consist of:

- A base layer with the primary color pigment.

- A mid-layer with metallic flakes, often controlled by a procedural noise map to give it sparkle and depth.

- A clear coat layer with its own reflection and glossiness values to simulate the protective finish.

This same principle applies to glass (with thickness and subtle color absorption), brushed metal, and textured plastics. You can even add subtle imperfections like dust or faint scratches using layered materials blended with procedural masks for ultimate realism.

Lighting and Environment Setup

The final piece of the rendering puzzle is context. A great model in a vacuum looks sterile. For studio-style automotive rendering, you’ll use a combination of area lights and an HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image) for environment-based lighting and reflections. The HDRI provides rich, realistic reflections across the car’s body, revealing every curve. Fine-tuning camera settings, like focal length and depth of field, is crucial for achieving that professional, photographic quality.

The Real-Time Imperative: Optimizing for Game Assets

When preparing a 3D car model for a game engine like Unreal Engine or Unity, the entire philosophy shifts. Performance is king. Every polygon and every texture pixel counts. The goal is to create the *illusion* of high detail while maintaining a smooth frame rate.

The Art of Retopology and Polygon Budgeting

The multi-million polygon model from our render scene would instantly bring a game to a halt. The first step is creating a low-polygon, game-ready mesh. This process, known as retopology, involves creating a new, simplified mesh that matches the silhouette and form of the high-poly source. The target polygon count, or “poly budget,” varies wildly:

- Hero Player Vehicle (PC/Console): 100,000 – 300,000 triangles

- AI Traffic or Secondary Vehicle: 20,000 – 80,000 triangles

- Mobile Game Vehicle: 5,000 – 20,000 triangles

This new mesh must be incredibly efficient, using the fewest polygons possible to describe the shape, and must be entirely triangulated for the GPU.

LODs (Level of Detail): The Key to Performance

A player will only ever see a car up close for a fraction of the time. As it drives away, the high detail becomes unnecessary and wastes performance. This is where LODs come in. A typical vehicle asset will have several LOD meshes:

- LOD0: The highest quality mesh, seen up close (e.g., 150k triangles).

- LOD1: A reduced version, seen from a medium distance (e.g., 70k triangles). Interior might be simplified.

- LOD2: A further reduction, seen from a distance (e.g., 30k triangles). Wheels might become simple cylinders.

- LOD3/4: Extremely simple meshes, sometimes just a handful of polygons, for when the car is a speck on the horizon.

Game engines automatically switch between these models based on the camera’s distance, saving massive amounts of processing power.

Baking: Transferring Detail from High to Low

How do we retain the visual fidelity of the high-poly model on our low-poly game mesh? The answer is baking. This process projects the surface details from the high-poly model onto the textures of the low-poly model. The most critical baked map is the Normal Map, which fakes the lighting information of small details like vents, bolts, and panel lines, making the flat low-poly surface appear three-dimensional. Other common baked maps include Ambient Occlusion (for soft contact shadows) and Curvature (for procedural texturing).

Texturing and Materials: A Tale of Two Workflows

Just as the geometry pipeline diverges, so too does the approach to materials and textures. High-end rendering and real-time engines handle them in fundamentally different ways.

PBR for Real-Time: The Metallic/Roughness Workflow

Game engines use a Physically Based Rendering (PBR) material system. The most common workflow is Metallic/Roughness. Instead of complex, layered shaders, materials are defined by a series of simple texture maps:

- Albedo/Base Color: The pure color of the surface.

- Metallic: A grayscale map defining which parts are raw metal (white) and which are non-metal (black).

- Roughness: A grayscale map defining how rough or smooth a surface is, which controls the sharpness of reflections.

- Normal: The map we baked earlier to add fake detail.

- Ambient Occlusion: Adds contact shadows.

For efficiency, these grayscale maps are often “packed” into the RGB channels of a single texture file to reduce memory usage.

UDIMs vs. Texture Atlasing

The UDIM workflow used for rendering, with its multiple texture sets, is terrible for game performance as each one requires a separate draw call. For game assets, the opposite approach is taken: texture atlasing. All the UVs for different parts of the car (body, interior, trim, etc.) are carefully arranged and packed into a single, square UV space (e.g., 0-1 space). This allows a large portion of the car to be textured using a single material and texture set, drastically reducing draw calls and improving performance.

Case Studies: Applying Theory to Practice

Let’s look at how these principles apply in real-world scenarios, starting with a premium model from a source like 88cars3d.com.

Case Study 1: Automotive Configurator in Unreal Engine

An interactive car configurator needs high visual quality but must run smoothly. You’d start with the high-poly model and create a single, optimized “LOD0” mesh around 200,000-400,000 polygons. You wouldn’t need aggressive LODs since the camera is always close. You would bake high-quality normal and AO maps and use 4K PBR textures. Unreal Engine’s material editor would be used to create a high-quality car paint shader that allows for real-time color changes.

Case Study 2: TV Commercial Close-Up in 3ds Max & V-Ray

For a cinematic shot focusing on a headlight, no detail is too small. You would take the source headlight model and apply 2-3 levels of TurboSmooth. You would model the individual LED bulbs, the fine textures on the plastic reflectors, and even the subtle seams on the housing. The glass material would have accurate Index of Refraction (IOR) and slight imperfections. The polygon count for this single component could easily exceed that of an entire game-ready car, but the result would be indistinguishable from reality.

Case Study 3: Mobile Racing Game in Unity

Performance is the only priority here. You’d create a heavily optimized LOD0 of around 15,000 triangles. The interior would be a very low-poly mesh with a baked texture. All UVs would be atlased into a single 1024×1024 texture set. Details like the grille or vents would be represented entirely by the normal map and transparency on the texture. There would be 3-4 aggressive LODs, with the final one being just a few hundred triangles.

Conclusion: The Right Tool for the Job

The journey of a 3D car model from a master file to a final product is a tale of two distinct, highly specialized paths. The path of automotive rendering is one of addition and refinement, pushing detail and complexity to achieve photographic perfection. The path of game assets is one of clever reduction and illusion, baking detail into textures to achieve maximum performance.

Understanding these differences is crucial for any 3D artist. It allows you to make informed decisions, plan your projects effectively, and adapt any source model for its intended purpose. The key takeaway is that starting with a meticulously crafted, well-organized, and topologically sound source model—the kind of professional asset found on platforms like 88cars3d.com—provides you with the perfect foundation, giving you the flexibility to build either a cinematic masterpiece or a high-performance interactive experience.