From Photorealism to Real-Time: A Technical Guide to Mastering 3D Car Models

From Photorealism to Real-Time: A Technical Guide to Mastering 3D Car Models

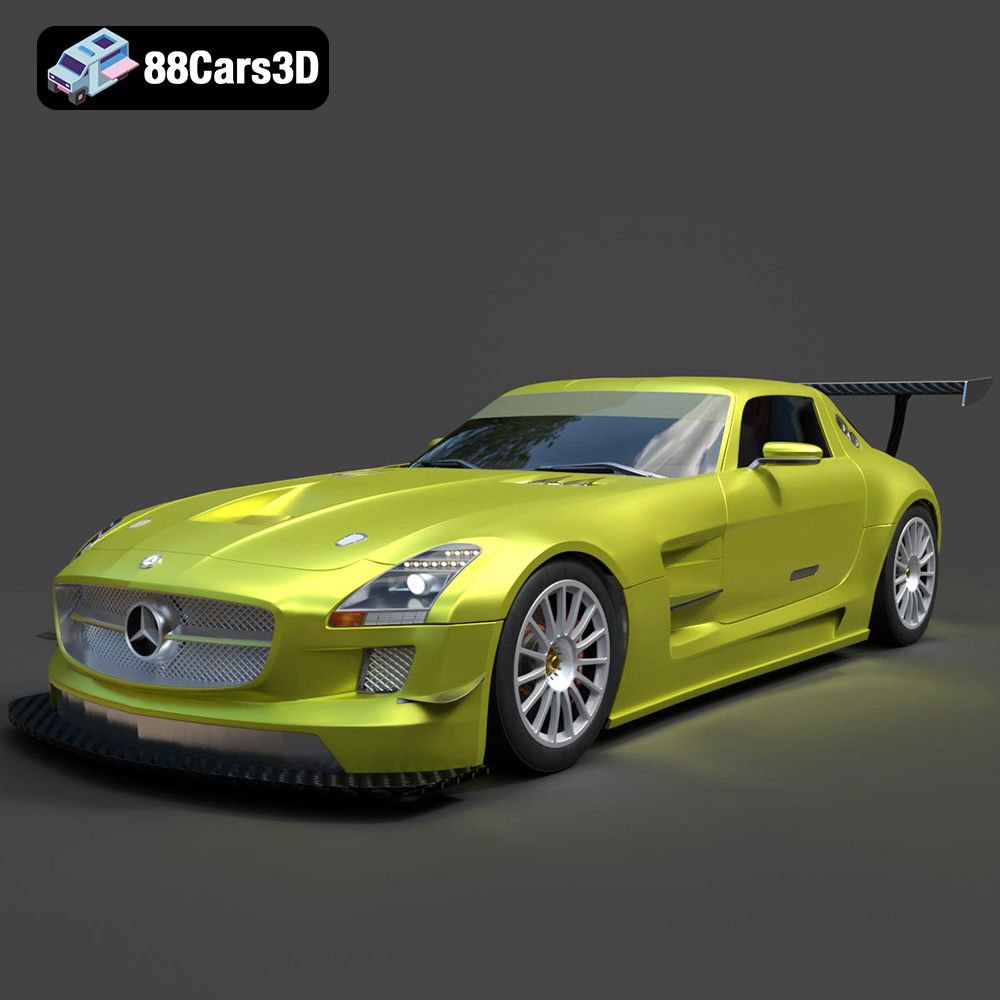

From blockbuster films and hyper-realistic car commercials to the latest AAA racing games, high-fidelity 3D car models are the driving force behind today’s most compelling digital experiences. They are more than just digital replicas; they are complex assets, a fusion of artistry and technical precision. However, acquiring a beautifully detailed model is only the first step on the road to a stunning final product. The real magic lies in understanding how to prepare, optimize, and deploy these assets for specific applications.

This comprehensive guide will take you under the hood, exploring the technical workflows required to transform a production-ready 3D car model into a photorealistic render or a high-performance game asset. We’ll delve into the critical details of topology, materials, lighting, and optimization, providing actionable insights for artists and developers alike. Starting with a meticulously crafted asset, like the models found on 88cars3d.com, provides a superior foundation, but mastering these subsequent steps is what separates amateur results from professional-grade visuals.

Anatomy of a Professional 3D Car Model

Before diving into application-specific workflows, it’s crucial to understand the fundamental characteristics that define a high-quality 3D car model. These core components dictate the model’s flexibility, visual fidelity, and suitability for various pipelines.

Topology, Edge Flow, and Polygon Count

The mesh is the skeleton of the model. Professional models are built with clean, quad-based topology. This means the surface is primarily constructed from four-sided polygons. This approach is superior to triangles (tris) or n-gons (polygons with more than four sides) because it allows for clean, predictable subdivision and deformation. The edge flow should follow the natural curves and contours of the car’s body panels, ensuring that reflections flow smoothly and highlights are captured accurately. For high-end automotive rendering, models often have a base poly count of 500,000 to 2 million polygons, designed to be used with subdivision modifiers (like 3ds Max’s TurboSmooth or Blender’s Subdivision Surface) for perfectly smooth results.

UV Unwrapping and PBR Texturing

UV mapping is the process of “unflattening” the 3D mesh into 2D space so textures can be applied correctly. A professional model will have clean, non-overlapping UVs with minimal distortion. This is critical for applying detailed textures like dirt, decals, or complex material effects. Modern workflows rely on Physically Based Rendering (PBR), which uses a set of texture maps to simulate how light interacts with a surface. Key maps include:

- Albedo: The base color of the surface, void of lighting or shadow information.

- Roughness/Glossiness: Controls how rough or smooth a surface is, which dictates how sharp or blurry reflections are.

- Metallic: A black-and-white map that tells the renderer which parts are metal (white) and which are non-metal/dielectric (black).

- Normal: Adds fine surface detail (like leather grain or tire treads) without adding extra polygons.

Scene Hierarchy and Naming Conventions

A well-organized model is a dream to work with. Instead of a single, monolithic mesh, a professional car model is broken down into a logical hierarchy of named parts. At a minimum, you should expect objects to be separated and named correctly, for example: `Body_Main`, `Wheel_FL` (Front-Left), `Door_Driver`, `Glass_Windshield`, `BrakeCaliper_FR`. This clean organization is essential for rigging the car for animation, applying different materials with ease, and isolating specific components for edits or optimization.

Workflow for Photorealistic Automotive Rendering

The goal of automotive rendering is to create an image that is indistinguishable from a real-world photograph. This requires a meticulous approach to materials, lighting, and camera setup, leveraging the full potential of a high-polygon model.

Advanced Material and Shader Creation

The car paint shader is arguably the most complex material on the model. A convincing paint material is layered. In a DCC application like 3ds Max with V-Ray or Blender with Cycles, this is achieved by blending multiple components:

- Base Coat: The primary color of the paint.

- Metallic Flakes: A separate layer using a procedural noise or flake map to simulate the small metallic specks within the paint. This layer has high metallic properties and a slightly different color to create depth.

–Clear Coat: A top layer with high reflectivity and a specific Index of Refraction (IOR, typically ~1.5-1.6) that sits above everything else, providing the glossy, protective finish.

Other materials like chrome, rubber, glass (with proper thickness and IOR), and leather (with subtle normal map details) must also be carefully crafted using the PBR principles to achieve true realism.

Lighting with High Dynamic Range Images (HDRI)

The single most important element for realistic reflections and lighting is an HDRI. This is a 360-degree panoramic image that contains a vast range of light intensity data. When used to illuminate a 3D scene, it provides not only the light source but also the complex reflections that make a car look grounded and real. For studio shots, a combination of an HDRI for ambient light and fill, along with manually placed area lights (key, fill, rim), can provide more artistic control over highlights and shadows.

Camera and Final Render Settings

Treat the 3D camera like its real-world counterpart. Use a physical camera model and adjust settings like F-Stop (aperture) to control depth of field, shutter speed to control motion blur for moving shots, and ISO for exposure. For the final output, rendering in separate passes (e.g., beauty, reflection, ambient occlusion, z-depth) gives you maximum control during post-production in software like Photoshop or Fusion. This allows you to fine-tune reflections, shadows, and color grading non-destructively.

Optimizing 3D Car Models for Real-Time Game Engines

Creating game assets is a completely different challenge. Here, performance is king. The goal is to preserve as much visual detail as possible while ensuring the model runs smoothly at 60 frames per second or higher in engines like Unreal Engine or Unity.

Polygon Reduction and Level of Detail (LODs)

Imagine you’ve acquired a stunning, 2-million-polygon model from a marketplace like 88cars3d.com. This is your “source” or “high-poly” model. To make this a viable hero game asset, its polygon count must be drastically reduced. This process, called retopology, involves creating a new, clean, low-polygon mesh that matches the silhouette of the high-poly version. A typical “hero” car for a modern game (LOD0) might be between 80,000 and 200,000 triangles.

Furthermore, you must create several even lower-poly versions called Levels of Detail (LODs). As the car gets further from the camera, the game engine automatically swaps in a simpler model:

- LOD0: 80k-200k tris (for close-ups)

- LOD1: 40k-80k tris (medium distance)

- LOD2: 15k-30k tris (far distance)

- LOD3: <10k tris (very far distance, often with simplified geometry)

Baking High-Poly Details to Normal Maps

How do we retain the intricate details of the high-poly model on the low-poly game asset? The answer is normal map baking. This process projects the surface detail from the high-poly model onto a texture that is applied to the low-poly model. The normal map tricks the game engine’s lighting system into thinking the low-poly surface has all the panel gaps, vents, and curves of the original, creating the illusion of high detail at a fraction of the performance cost. This baking is typically done in specialized software like Marmoset Toolbag or Substance Painter.

Texture and Material Optimization

In a game engine, every material and texture adds to the memory footprint and the number of draw calls (requests from the CPU to the GPU). To optimize this, artists often use texture atlases, where UVs for multiple separate parts (like the brake calipers, suspension, and engine parts) are combined into a single UV layout, using one material and one set of textures. This significantly reduces draw calls. Additionally, textures are often smaller (1K or 2K instead of 4K or 8K) and utilize efficient compression formats to keep memory usage low.

Case Study: A Workflow from 3ds Max to Unreal Engine 5

Let’s walk through a simplified, practical workflow for bringing a production model into a real-time environment.

Preparation in 3ds Max

Start with the high-poly car model. First, ensure the scale is correct (1 unit = 1 centimeter is common for UE5). Clean up the hierarchy, grouping objects logically. Create the low-poly game mesh (LOD0) and its subsequent LODs using retopology tools. Carefully unwrap the UVs for the low-poly mesh, ensuring efficient use of texture space. Assign different Material IDs to surfaces that will have different materials (e.g., body paint, glass, rubber). Position all objects at the world origin (0,0,0) and reset their transforms.

The Critical FBX Export

Exporting from your DCC application to the game engine is a step where many things can go wrong. Use the FBX file format. Key settings to check in the 3ds Max FBX exporter include:

- Geometry: Ensure “Smoothing Groups” is checked. This is vital for correct surface shading.

- Axis Conversion: Set the Up Axis to “Z-up” for Unreal Engine.

- Units: Export in Centimeters.

- Embed Media: Uncheck this. It’s better to import textures separately into the engine.

Assembly and Material Setup in Unreal Engine 5

Import the FBX file into your Unreal project. It’s best practice to import the car parts as separate static meshes. You can then create a Blueprint Actor to act as a container for the car. Drag the various static meshes (body, wheels, etc.) into the Blueprint’s component list and assemble them. Next, create a master car paint material that exposes parameters like color, roughness, and metallic flake intensity. From this master material, you can create limitless Material Instances for different color variations without duplicating textures, which is an incredibly efficient workflow.

Advanced Applications and Final Touches

Beyond static images and basic game implementation, these versatile assets can be pushed even further.

Rigging for Animation and Interactivity

A properly organized model can be easily rigged. A simple rig would involve setting up controllers to spin the wheels and steer the front axle. A more complex rig could control the opening of doors, the hood, and the trunk, or even simulate a working suspension system. This is essential for animated cinematics, interactive car configurators, and playable vehicles in games.

Post-Production Polish

Whether it’s a still render or a gameplay video, post-production is the final 10% that adds the polish. For renders, this means compositing passes in Photoshop or Nuke to add lens flare, chromatic aberration, film grain, and perform final color grading. For real-time applications, Unreal Engine’s Post-Process Volume allows you to do much of this in-engine, adjusting bloom, exposure, and color lookup tables (LUTs) to achieve a stylized, cinematic look.

Conclusion: The Asset is Just the Beginning

A high-quality 3D car model is an incredible starting point, but it is not the final destination. The journey from a raw digital file to a breathtaking piece of visual media is paved with technical knowledge and artistic decisions. Understanding the fundamental differences between preparing a model for photorealistic automotive rendering versus optimizing it for real-time game assets is the key to unlocking its full potential.

By mastering topology, materials, lighting, and the specific optimization pipelines for your chosen application, you can transform any well-made model into a centerpiece for your portfolio, film, or game. Starting with a professional-grade asset saves invaluable time on modeling and cleanup, allowing you to focus your energy on these crucial, value-adding steps that truly bring a digital vehicle to life.